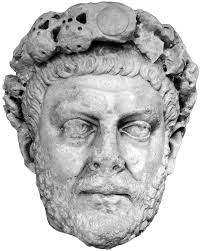

Diocletian’s reign and the fall of the Western Roman Empire – Sam Christmas

Introduction

The question at stake is “ to what extent did Diocletian’s reign contribute to the fall of the Western Roman Empire?”

The aim of the project is to evaluate Diocletian’s effect on the empire’s longevity by examining the key factors that led to its arguable collapse in 476 CE over a century and a half later. This collapse occurred with the deposition of emperor Romulus Augustulus by Odoacer, leader of the Germanic foederatii (allied mercenaries) who were formerly in the employ of the Roman Empire. It is imperative to discover the extent of Diocletian’s responsibility for the Western Empire’s collapse. Diocletian’s decision to create the tetrarchy and thus divide the empire was a distinctive shift in imperial policy from a more autocratic system to a collegiate style of government. Therefore, this in itself suggests the significant impact he had upon the empire and its longevity and thus deserves to be investigated in its own right.

Diocletian’s reign will be evaluated by its effect upon those key factors: firstly, the weakening of the Roman legions; secondly over-expansion and politically instability; and thirdly barbarian invasions and migrations; economic problems and finally, the rise of the Eastern Roman Empire. Each of these five factors will be separately examined in order to reveal the total effect of Diocletian’s reign upon the Western Roman Empire’s fall in 476 CE.

Military Decline

The most important of Diocletian’s reforms (at least in relation to the state of the empire almost two hundred years later) were those which dealt with the empire’s military due to its essentialness to the Roman way of life as well as its survivable ensures its prominence among the reforms and justifies this factor’s length.

By the late third and fourth centuries CE, the seemingly invincible Roman legions of Julius Caesar and Augustus were nowhere to be seen. Increasingly politically instability, civil wars and incompetent leadership revealed Rome’s weakness, previously unseen by the barbarian tribes. The defeat of Phillip the Arab in 249 CE, killed at the Battle of Beroea by a rebel Roman army, triggered a period of instability for the empire for the next thirty years. With the decline of the stability of the Imperial throne, the role of the legions became increasingly important. Now, however, their attention was internal rather than guarding the empire’s borders. Indeed the importance of the legions is conveyed by Emperor Septimus Severus’ last words to his two sons, “get along very well and pay the soldiers a lot and don’t care for anything else.” This implies the extent of necessity of the military for a successful regime.

Because of the various conflicts over the imperial throne in the third century, which the armies were at the heart of, the borders were often unprotected. So when Diocletian came to power he realized that the empire needed military reorganization and thus “the empire’s military defense became the ruler’s main duty”. Accordingly, he turned his attention to this, the empire’s most pressing concern. One of the greatest issues for the Roman Army was that it “lacked an appropriate amount of soldiers defend its borders.” This inherent problem contributed to the empire’s collapse in the fifth century CE, so its importance justifies an evaluation of Diocletian’s solution. By the beginning of the second century CE there were 750,000 people in the city of Rome itself yet by the fourth century there were only 75,000. This indicates the problem of the population decline which links inextricably to the decline of the military. While this is a dramatic decrease this shouldn’t be taken out of context because of the shift of the imperial capital from Rome to Milan (Ravenna) in the West and Nicomedia (Asia Minor) in the East.

One of Diocletian’s solutions to this issue was the mass conscription of Germanic tribesmen into the legions. While there had always been a significant amount of non-Roman legionnaires and auxiliaries, by the fourth century only one percent of the Roman Army was Italian, “the main way of forming the army was recruiting volunteers, mostly barbarians”. This process was indeed amplified by Diocletian so much so that in the fourth and fifth centuries, the Roman word for soldier was changed from ‘miles’ to ‘barbarus’. This indicates the extent of the concentration of barbarian soldiers serving in the Roman army. This had two consequences, the first of which was a lack of loyalty solely to Rome. For the leader of the Germanic soldiers who attacked Rome and deposed Romulus Augustus in 476, was Odoacer, who served as an auxiliary officer was a series of the foederatii. This indicates that Diocletian’s reforms ensured a rapid incline of the concentration of barbarian soldiers, which meant that Rome’s armies owed allegiance either to their province or general rather than Rome or the emperor. In combination with this, the second consequence of ambitious officers who, increasingly, lacked the restraint of even the veneer of loyalty to the empire; this was also a significant factor. A fine example of this is Odoacer, who after wrestling power from his liege lord, crowned himself the first king of Italy. Yet, it would be wrong at assume that by any means all of the officers of barbarian origin were disloyal or any more ambitious than their Roman counterparts. Stilicho, half-Roman and half-Vandal, served the emperor Theodosius I so gallantly and loyally that he was awarded the hand of the emperor’s niece, as well as being titled by Roman courts poets such as Claudian “as a fearless defender of Rome”. It would be wrong to assume that only barbarians had the monopoly on ruthless ambition, as the last Emperor’s father, violently deposed his son’s predecessor, Julius Nepos in 475, violating his oaths of loyalty and disregarding any notions of honourable service.

In the short term, Diocletian’s solution was highly effective and successful as he provided an immediate increase in the amount of soldiers and provided ample forces with which he could effectively garrison and protect the empire’s borders. Yet, in the long term, this reform was detrimental to Rome’s survival. This was due to the creation of an army whose loyalty was no longer guaranteed in the same way as had in previous centuries, although this had been slowly occurring for the last hundred years. However, this was amplified by Diocletian’s mass acceptance of Saxons, Iberians Franks, Alamanni, Goths, Vandals and Burgundians as conscripts and officers into the army rather than the more reliable provincial subjects of the East, Africa, Gaul and Spain as well as, of course, of soldiers from the Italian peninsula. This increased concentration of less reliable Barbarian soldiers within the Roman Army led to the mercenary foederatii forces who eventually betrayed Rome and usurped its last Western Emperor and created the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy.

Another of Diocletian’s military reforms was to divide the army into two corps: the limintanei, or “border unit” an immobile garrison forces that protected the empire’s borders such as the Danube and the Scottish-Anglo border, and the comitatenses, the mobile response legions that were located on strategically suitable spots”. This improved Rome’s defense system by providing a greater presence on the borders that for the extent of the next twenty years, ensured that Rome was not as vulnerable to barbarian invasions as it had been. Yet, this was subverted by Constantine’s decision to move the army from the borders to the town and cities in the beginning of the fourth century. However, Diocletian’s efforts were successful and certainly were not detrimental to the empire’s survival; in fact, they achieved the opposite. Indeed, “with these measures, Diocletian improved the military situation and provided for its better defence”. As well as improving its border security, he also recognized the increased importance of cavalry within armies in Late Antiquity. This allowed the absorption of Hunnic horse archers, as well as the heavily armored Eastern cataphracts (heavily armoured cavalry), possibly an ancestor of the Western European medieval knight, which were implemented successfully to counter the cavalry heavy army of the Eastern barbarians.

In conclusion, Diocletian’s decision to create the two different corps of the Roman Army ensured that, according to Zosimus, the “frontiers of the Roman empire were everywhere studded with cities and forts and towers… and the whole army was stationed along them so that it was impossible fort the barbarians to break through them.” His reforms created an efficient border defense system which was beneficial and may have well held the barbarians at bay for several centuries, even though it was undone by Constantine the “Great”. Another benefit of the reforms was the sudden increase, via mass barbarian conscription, in the amount of soldiers from which the state could draw thus enhancing its defensive capabilities. However, this short term solution was harmful as it, over the following two centuries, eroded the quality of soldiers as well as their loyalty leading to the usurpation of the emperor by barbarian foederatii in service to the Empire. Diocletian’s reforms were successful as they dealt with the immediate problems, however, they themselves proved to undermine the Empire, suggesting a sense of inevitably to its eventual decline. This reinforces the notion that Edward Gibbons’ belief holds some merit as “instead of inquiring why the Roman Empire was destroyed, we should be surprised that it had subsisted so long.”

Over-Expansion and Political Instability

This factor was, again arguably, one of the most significant threats facing the Roman Empire in the third and fourth centuries CE. This was because Rome’s sheer amount of territory made it administratively and logistically extremely difficult to govern as it was unable to communicate quickly or effectively enough to secure its borders. “By the year 284 CE, the Empire had grown too vast to be ruled by a single central authority”. Diocletian responded to this problem with the greatest dynamism. His most famous reforms, not just in relation to the question at hand, were the division of the empire and the creation of the tetrarchy in 293 CE, although the process began in 285 CE.

It began with his victory over the last rival claimant for the imperial throne at the battle of Margus, in 285 CE. Immediately he realized that the empire was too large to be managed and ruled effectively and successfully. Although he was a competent general he realized that the empire needed effective military commanders as “he was distinguished as a statesman rather than as a warrior.” In November 285 he “immediately appointed his trusted friend Maximian emperor, a good soldier and talented, although he was semi-civilized.” At this time he was promoted as a Caesar (junior emperor) in order to assist Diocletian in running the Empire as he was sent to govern the Western half. This was the first start on the road to the creation of the tetrarchy. On 1st April 286 CE, Maximian was promoted to Diocletian’s equal, at least in terms of rank, as an Augustus (senior emperor) who governed the Western half while Diocletian governed the Eastern half. By 293 CE, each Augustus had adopted as his son a junior emperor: Constantius for Maximian in the West and Galerius for Diocletian in the East. Thus, “Diocletian subverted the monarchial government of the previous dynasties of Imperial Rome” and transformed it into a collegiate government based on the principle of a meritocracy. This hypothetically would serve Rome in the most successful manner rather than the less reliable dynastic succession which had produced very unsuccessful emperors such as Commodus and Elagabalus.

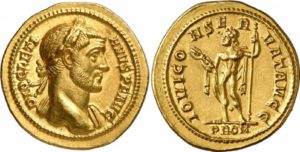

This succession was cemented both by a marital link and a religious one. Galerius married Diocletian’s daughter, while Constantius wed Maximian’s stepdaughter, thus acting as a catalyst of political stability. After 287, he called himself Jovius (Jove) and Maximian was named Herculius (Hercules), signifying that they had been chosen by the gods and predestined as participants in the divine nature. Thus, they were charged with divine wisdom for Diocletian and heroic energy for Maximian. This cemented the theme of rule by divine right and helped to establish them with the upmost clarity as the rulers of the Roman world. While this may have been following the precedent set for them by Aurelian and Probus, in theory it created set and fluid system of succession; however, it only lasted until 313 CE with the subversion of power when internecine conflict arose, leaving Constantius’ son, Constantine as the sole ruler in 324 CE. Yet it proved to be effective while it lasted. In the East there was a rebellion led by the rogue general Achilleus in 296 CE in Egypt. This was dealt with very effectively and was crushed. Diocletian was able to deal with the threat as an offensive role, while Galerius assumed the governance of the east in his senior’s absence. He was able to defend against the Persian armies of king Narses who had lead his army into the Roman province of Syria; defeated him and forced the surrender of seven satrapies north of the river Tigris. This is just one example which demonstrates the effective nature of the collegiate government: it allowed a combination of offensive and defensive attacks which culminated in the efficient defense of the Empire. Suggesting that Diocletian’s reforms were effective and did not contribute to the Empire’s decline, but actually prevented it. However, this success is subverted by the fact that Diocletian’s tetrarchy only survived until 313 CE and, therefore, its success and survival was correlative to the survival of its creator.

With this new system, the Empire was divided into four spheres of influence with the two senior Augustii governing the most strategically important provinces. Diocletian governed Thrace, Egypt and the Asian provinces, while Maximian’s area of control was the Italian peninsula as well as the province of Africa. In support of their Augustii, Constantius held Gaul, Spain and Britain while Galerius held dominion over the Danube frontier and the Illyrian provinces. The creation of two capitals of the Empire also increased stability as both halves of the Empire now had a clear political power base as in the west Maximian chose Milan and it “assumed the splendor of an imperial city” due to its proximity to the Alps in order to be able to react more quickly to the German tribes. Diocletian chose Nicomedia as his capital due to its proximity to the Euphrates. Thus it made the military and civil reactions to problems facing the Empire more efficient and thus more effective.

As well as making clear the new political power bases, Diocletian also “reduced and cancelled the Praetorian’s privileges” because he recognized that the Guard were, and had increasingly become, a medium for political instability as they had assassinated emperors such as Caligula, Caracalla and Elagabalus, as well as crowning other emperors such as Claudius. Instead of the Praetorians, he chose two Illyrian legions, for that is where he originated, to act as the new imperial security force. This made the issue of the reliability of the imperial bodyguard void as they owed their new and privileged status to their master which was very different from the long established Praetorians.

Another solution to the issue of political instability due to overexpansion was when Diocletian doubled the number of provinces to 100, ensuring that there was less of a risk of rebellion as governors had a decreased economic base as well as having fewer soldiers to call upon. This was an essential reform as Rome’s history was plagued with dissident generals and governors, most famously Carausius who revolted and claimed power in Britain, claiming himself emperor and ruling for nearly ten years until he was assassinated by one of his commanders who wanted to appease Constantius who had just led a fleet to Britain. He also created thirteen dioceses, which were groupings of the provinces into larger circumscriptions as “having created so many provincial ggovernors, Diocletian evidently found that their supervision too severely taxed the central government, even though this was divided into four sections.” Each one of the vicarii was answerable to one of four praetorian prefects; one for each tetrarch, thus achieving a clear hierarchy that made management efficient and thus reduced the scale of the problem of the Empire’s vastness as there was a clear order of government that achieved stability through clarity of governance.

The division of the empire seemed to be the most viable option as it solved the problem of political instability because of over-expansion by firstly dividing the empire into four spheres of influence for each of the tetrarchs, each of whom was assisted by a praetorian prefect, who managed their vicarii who in turn managed the governors of their diocese. This divided the empire into smaller sections which made governance more manageable especially with the creation of a clear hierarchy. He established a clear transition of power via the tetrarchy based upon adoption and abdication. He also solidified the imperial throne by linking the Augustii with the divine. His removal of the Praetorian’s prominence was the first move to extinguishing their significance as a political organization that had a monopoly over their influence of imperial succession. He proved to be first emperor to ever retire as “no other emperor had ever formally abdicated his position before his death.” This signifies a uniqueness that demands examination in its own right, but, in the context of creating stability, it speaks volumes in his favour as reformer who solved, or at least attempted, the problems facing the Roman Empire. In particular, he addressed the political instability, related to over-expansion of the empire’s boundaries and territories. Yet, possibly the fatal flaw of the tetrarchy, arguably hostile to the most significant reform, was that both Maximian and Constantius both had sons. Because of this paternal favour over-ruled the meritorious electoral system that was based upon non-familial adoption.

The Barbarian Threat

Arguably, the most obvious of the features of the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Gibbons would argue, was that barbarian migrations and invasions “would be insufficient to bring the sophisticated military and political of the west into ruin”. Other historians suggest that military defeats such as the Battle of Adrianople, 9th August 378 CE, with the defeat of the Eastern Roman imperial army under the Emperor Valens and the death of the emperor, were essential to the decline in Roman power. This Roman defeat was the beginning of the detachment of the Eastern Empire from the West as the East was not eager to repeat the huge casualties of the battle where c. 20,000 Eastern Roman soldiers died. It also signified the rise of the Goths as a major military power within the Roman Empire.

Also the sacking of Rome, once in in 410 CE by the Visigoth King Alaric and again in 455 CE by the Vandals, inflicted heavy defeats upon the Western Roman Empire. Although these losses were important practically due to the amount of deaths suffered and wealth stolen by Rome, most important was the message of Rome’s painfully obvious vulnerability to the Barbarian threat. This vulnerability was finally exploited in 476 CE by Odoacer who usurped the fourteen-year-old emperor and forced thus abdication and created the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy in the process. Therefore, it would not be pertinent to suggest that the barbarian threat was a significant reason to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

In relation to Diocletian’s reforms to the barbarian threat in the late third and early fourth centuries CE. The establishment of Milan as the imperial capital because it was closer to the barbarian Germanic tribes is an indicator of Diocletian’s response to these threats. He used punitive campaigns into Mesopotamia against the Persians in 298 which ensured that the Persians under king Tiridates were never a threat for the duration of Tetrarchy. Also the doubling of the army from c.300,000 to c.600,000 was another response to the Barbarian threats. His response to the Barbarian threat was to ally with them to create foederatii whose loyalty was meant to belong to Rome; however, this policy of creating federation of allied barbarian tribes within the empire’s borders proved to be a popular one with future emperors. These men allowed barbarian tribes, often after being threatened with military reprisals, to migrate within Roman territory. However, these tribes were the ones who sacked Rome in 410CE and 455CE respectively and, therefore, it would be credible to attribute some of the blame upon Diocletian for this. Yet, these invasions of Rome never took place under the strong leadership of Diocletian or any of his immediate successors but under the reign of Honorius in 410 CE, widely considered as one of the worst emperors as it was within his reign that Rome was sacked for the first time in 800 years. The later sack of Rome in 455 CE occurred with no emperor alive, as he had been murdered three days before.

Diocletian dealt with the barbarian threats successfully, yet his solutions required strong leadership and internal stability within the Roman Empire itself so later on when the western empire lacked both of these things, Diocletian’s solutions became the problems that led to the empire’s collapse.

The Economic Problems

As well as the military, logistical and political problems, the empire was undergoing significant economic inflation in the mid-3rd century BCE. This was partly due to the chaotic, and often violent, successions from one emperor to the next. The silver coinage had been reduced dramatically in weight, size and silver content. Also the falling population in the second and third centuries there was a labour deficit, which crippled the empire’s production rate which hampered the economy.

“Diocletian made valiant efforts to re-establish a sound currency and thereby to stabilize prices.” He re-established the gold aureus in order to reduce inflation; this was the first attempt to reform the Roman monetary system. Next, he decided to try and stabilize the denarius, returning its weight back to that under Nero over two hundred years ago. Yet, this reform was not enough. “Military costs were by far the most expensive” as there were arguably 60 legions, which had been doubled from c.30, and each soldier was paid 750 denarii per year. This compares to the 25 legions under Augustus, where each soldier was paid 225 denarii. However, the comparisons are not as dramatic as it might seem. The legions of Augustus were comprised of 5000 men whereas under Diocletian they had possibly consisted of around 1000. Also the role of the legions had become increasingly essential to imperial stability so their greater reward matched their more significant role. So the imperial army was too large for the economy to be sustainable. Yet, his new coinage did not excite any confidence and as the coins flooded the market, the economy required new sets for coinage just to keep pace with inflation. It was becoming apparent that Diocletian’s reforms were not being successful. In 301, Diocletian attempted to stem the tide with Edictum De Pretiis Rerum Venalium (edict on control of maximum prices) which fixed maximum prices and wages in order to try and control the economic market as a medium for financial stability. Yet, there was a plethora of problems such as no allowance made for transportation costs, therefore varying the costs dramatically over the empire and undermining the entire point of the edict. As the ancient Christian chronicler Lactantius certainly believed, the edict was a failure as he stated that it had caused no consumer products to appear and there was much (Christian) blood spent and then, after realizing the edict’s failures, it was repealed. However, this scathing criticism must be taken in the context that he was a Christian in a time where there was extensive persecution of members of his faith. Therefore, he would already have an inherent hostility towards Diocletian, an advocate of persecution and religious suppression. Yet, Lactantius’ conclusion was correct as in the beginning of the fourth century CE, prices climbed and the edict was allowed to relapse into history.

“Diocletian also began the process of turning the Roman economy into a command economy.” As under his reign there was a rapid process of bureaucratization of the empire and he focused on having a central government who dictated how Rome’s economy would function to the local administration. The newly enlarged bureaucracy was severely criticized by Lactantius as the burden that the army and the civil service was intolerable: “There began to be fewer men who paid taxes than there were who received wages; so that the means of the husbandmen being exhausted by enormous impositions, the farms were abandoned, cultivated grounds became woodland, and universal dismay prevailed. Besides, the provinces were divided into minute portions.” Therefore his political reforms, while effective elsewhere, were detrimental to the empire’s economy and his financial reforms failed to solve this issue. This led to a breakdown in the economic powerbase of the empire ensuring that increases of taxes became the only way of stabilizing the Roman economy. Yet this did not work as the effects of the government taxes ostracized both the provincial Roman subjects as well as the Romans themselves from the urban elites. This meant that a gradual disenfranchisement occurred, and eventually there was a decline in the concern for the empire’s survival by the average citizen. Therefore, the fall of the Western Roman Empire can be partly attributed to Diocletian’s failure to fix Rome’s economic situation.

Rise of the Eastern Empire

The division of the empire is possibly one of the distinct relics of Diocletian’s reign. It did, make the empire easier to govern in the short term; however, they grew increasingly apart. Indeed, the strength of the Eastern Empire amplified the weaknesses of the West by its direct comparison. With the moving of the capital to Nicomedia, as Diocletian was the senior tetrarch, there was a clear shift of power from Rome to the East. Also the East’s economic superiority allowed greater development of its military and political strength. On account of this a sense of reliance on its oriental counterpart developed within the West, a move that had its origins with Diocletian, the senior tetrarch who ruled the East: signifying it as the senior branch of the empire. Such was the extent of the overreliance that, when the Eastern imperial army was defeated at the Battle of Adrianople in 376 CE, the East was forced to admit a large, organized body of gothic tribes within the frontiers of the empire. When these Goths started to rampage, the Eastern Romans were able to quell them so successfully that they began to shift their migration west. Because of this “the Western Empire found itself unable to deal with the simultaneous threats on the Rhine frontier, which collapsed in 406-7 CE.” Furthermore Constantinople, the future capital of the East, became too heavily fortified. This combined with a strong army and navy ensured that the barbarian threat “would sometimes be deflected westwards towards the more vulnerable western Balkans and Italian peninsula.”

Because of the East’s comparative success, this introduced a rivalry from the fifth century CE onwards as the Greek-speaking Eastern Empire grew in wealth while the Latin-speaking West descended into economic stagnation and decline. This division effectively meant that the Eastern Roman Empire would not continue to effectively support their weaker western counterpart. This proved to be the case when the Eastern Emperor Zeno the Isaurian refused to support his fourteen year-old western counterpart when Odoacer usurped him. Thus, through the division of the West and East of the Roman Empire which was amplified by Diocletian, his reforms ensured the downfall of the Western Roman Empire.

Conclusion

Each of Diocletian’s reforms of the five key factors that led to the fall of the Western Roman Empire musty be evaluated together to create a more complete picture of whether or not Diocletian’s reign did contribute to the empire’s fall in 476 CE. In the context of the problem of military decline, Diocletian effectively reformed the Roman army and indeed ensured that there were enough soldiers top effectively protect the empire so he succeeded. However, this when taken with hindsight contributed to political instability, via overexpansion, as it created a military, with a significant percentage of barbarian auxiliaries, which was disloyal and it failed to prevent the emperor’s deposition inn 476 CE. However, with the improved army, Diocletian was able to, with a combination of shrewd diplomacy as “he was distinguished as a statesman rather than as a warrior” to quell the barbarian threat.

At no point during his reign did the enemies of Rome manage decisively to defeat the imperial legions in sustained warfare. Yet, this is where Diocletian’s successes stop as he failed, somewhat uncharacteristically, to solve the economic crisis of the third and fourth centuries CE. As well as this one of his most well-known legacies, the division of the Roman world led to the rise of the Eastern Empire which outshone its Western counterpart and through its direct comparison, and rivalry, made it more vulnerable to barbarian attacks. The East’s ascension was begun by Diocletian who favored it as the half of the empire from which he ruled and made his capital.

So, overall, with the exception of the economy, Diocletian was a remarkably able emperor who left the empire with a succession system that was meritorious and efficient. However, his biggest failure was his naivety in relation to his fellow Romans. He underestimated the strength of familial loyalty over a greater sense of dedication to Rome and his successors ignored his plans. His strength, which managed to keep the empire together, was a not a virtue that was inherited by the majority his successors, especially on the Western throne. Yet, it would be wrong not to argue that he chose the only viable decision and that his policy to divide the Roman Empire, ensured the West’s survival for another 171 years and the East’s for over a millennium. Indeed, it would seem appropriate to deem the Eastern Roman Empire’s survival as his most significant legacy just as much as, if not more than; the fall of the Western Roman Empire could be partly attributed to him.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.