Film Studies: an undervalued subject? – Emi S

Film Studies, as a GCSE, an A-level or a degree, is often viewed as more of a hobby-turned-academic study rather than an academic subject in its own right with its own significant benefits to society. To many, it doesn’t appear particularly vocational nor particularly academically demanding. So what’s studying film actually like, and what is its place in today’s society?

Many notable people who have made a real difference to the way we perceive the world have studied film. You may have heard of Laura Mulvey, a feminist film theorist who coined the theory of ‘The Male Gaze’, which is not only seen in film, but can be applied to a range of other forms of fictive and non-fictive art alike. Slavoj Žižek, a prominent Slovenian socialist philosopher, actually had his origins in film theory and interrogation of avant-garde cinema, using this as a springboard for his career as a political philosopher.

Now, many comparisons I’ve heard is that Film Studies is just like English Literature, only instead of studying novels, plays and poetry, you study films. This is true to a large extent, as there are many parallels between applying historical context, social theories, and genre-dependent form to subject matter between the two courses. So, if they’re so similar, why do we view English Literature as having a greater academic reputation?

The truth lies in the perception of books vs. films. Literature has a much longer history than that of film, which was only invented 1895. Books are also more commonly regarded to be lengthy and needing an impressive attention span to consume, or at least greater than that needed to consume a film. Films, on the other hand, can be consumed easily by nearly anyone in a 2-hour window – this accessibility contrasts the exclusivity of finishing War and Peace, or Don Quixote, or a book written in Old English. However, it is the way in which film students consume film, analysing every frame for lighting, sound, camera work, mise-en-scène, hidden meanings, representations, metaphors, and other elements that really distinguish the study of film from simply watching the film. And some films aren’t always for easy consumption either – Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó is over an astounding 7 hours long.

Although I started my online Film Studies A-level in September and am lagging behind due to a myriad of excuses, I find myself honestly enjoying the studying so much that I don’t even mind doing it my free time. For me, the hardest part is actually watching the films themselves – having to set up the DVD player just to watch the film 3 times in a row, whilst making exhaustive notes so that I don’t have to watch it again a fourth, a fifth, and a sixth time is actually the most tiring part of the course. Studying the films and learning about context, narrative theory and representation is actually the highlight for me. Plus, next February, I get to make my own short film.

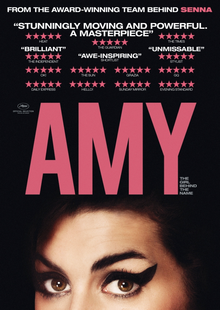

Learning about film context is fascinating, because it makes you question and interrogate what you are presented with in everyday life. For example, the documentary ‘Amy’, about Amy Winehouse, has made me ever more critical of the media I consume. The film exposes how manipulatively Amy Winehouse’s story was treated by the press, despite the film itself being a manipulated story. Even the use of home videos gives the story a sense of authenticity, yet it is integral to maintain a contextual perspective: everything you see is curated.

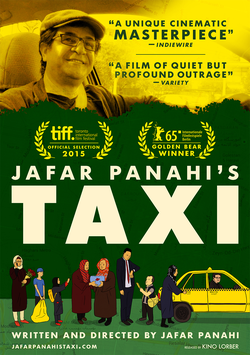

Other films question the ethics and politics of a regime, such as Jafar Panahi’s ‘Taxi Tehran’, which seeks to expose life under the Iranian theocracy and secret police, being filmed from a taxi camera. The irony here, of course, is that Panahi’s films are illegal in Iran; they only exist outside the bubble of the theocracy, having to be smuggled out and viewed with an outsider’s perspective.

Film is often a vehicle to express views. These can range from blatant attacks on political ideology to a subtle questioning of life’s more individual struggles. Ultimately, film is an interpretation of life, the same as art and literature is. The film industry is empire-like in today’s society, and it should be recognised as having a substantial academic reputation as well as a commercial one. Hopefully, this will become the case as new film movements emerge, reviving film as an art form rather than a commercially-focused project.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.