The German Economic Crisis of the 1920s – Joe Buckley

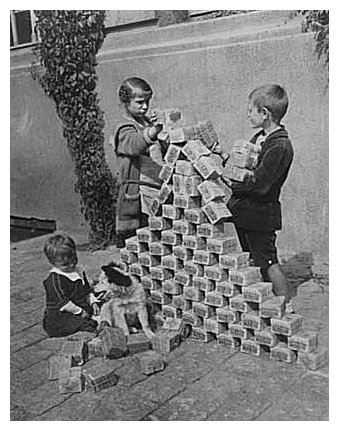

Among the most notorious economic crises the world has faced in the last century, perhaps none have had such a great effect on a West European country as the infamous hyperinflation that occurred in Germany following World War One. The many photographs of children playing with stacks of money and families simply burning the paper to help heat their homes clearly demonstrates the extent to which this affected families across the country. This rapid decrease in the value of the currency is a fascinating study as it highlights the instability of markets on a grand scale. Furthermore the subsequent, yet nonetheless slow, rebuilding of the economy through various policies is another interesting topic.

Perhaps it would be best to start where Germany’s economic problems truly began. That being the 1st of August 1914 when the nation declared war. This was because the German’s underestimated their opposition believing that the conflict would be swift and profitable for Germany due to the rather simplistic nature of the Schlieffen plan for which so many Generals had faith in. However as we now know this soon failed after Britain had unexpectedly followed through with its promise that if Germany invaded Belgium then Britain would have no choice but to enter into the war. What followed was over 4 years of campaigns among the allies and axis that brought destruction to infrastructure, homes and the lives of those that lived in them. By the end of the war Germany, expecting to win the conflict, had borrowed millions of what was then known as ‘Papiermarks’. This currency was introduced only 3 days into the war when the link between the ‘Goldmark’ and gold was abandoned. As well as this the damage Germany had caused to the other allied powers was monumental. The cost of this and Germany’s borrowing throughout the war were combined and were to be paid through the reparations set out in the Treaty of Versailles which Germany of course reluctantly signed on 28th June 1919. These reparations amounted to over what would nowadays be equivalent it $33 billion, a sum which at the time would be impossible for Germany to pay off within the foreseeable future. Yet this was not the case. This is because the victorious powers had divided the reparations up into three bonds, bonds A, B and C. The allies then decided that the ‘C’ bonds Germany did not have to pay even though they totalled over half of the sum as the C bonds were designed to deceive the public and appease those who had lost much to the war at Germany’s hands. Still the burden of this to Germany was even greater however as key sources of income for the economy had been taken by the allied powers under other terms in the Treaty. Two notable examples is the withdrawal of the Saar Basin coal mining from Germany for 15 years to be ruled under the League of Nations as well as the transfer of territory such as Alsace-Lorraines being restored to France. This crippled the nation’s capability to pay off the debt, hindering the economy for many years to come and increasing general public outrage and discontent. However the worst was yet to come for the German economy.

Following the ‘Great War’ the once powerful German Empire was succeeded by the Weimar Republic, a provisional government which had strong democratic influences. At the time the collapse of the empire was highly controversial as Germany had been under the rule of the Kaiser for many years and the population preferred a strong and authoritarian government to a more democratic and liberal form of government. This created chaos among the populace as the new found political freedom led to the formation of both the Spartacist factions and the Freikorps which were extreme left and right wing factions. These two warring factions worsened the economic situation that Germany had been found in after the Treaty of Versailles as the street clashes led to the destruction of infrastructure which limited the capacity of the economy to manage the enormous debt Germany was in at the time. As well as this the men involved in the two groups would have reduced the productivity of the Republic as they were destroying property and infrastructure when they could have been adding additional labour input to the economy.

Perhaps the most dramatic event was the occupation of the Ruhr by both France and Belgium which occurred between 1923 and 1925. This occurred due to the victors frustration with the Weimar Republic defaulting on their debts. This is because both nations’ economies were struggling themselves after much of their capital and land had been destroyed in the war and were therefore desperate for any money or resources they could get there hands on in an effort to restart the economy. This would primarily be through investing in infrastructure and rebuilding the many villages and towns damaged in the war-effort. This is because investment can lead to an increase in both the aggregate demand of the economy but if spent through supply-side policies such as more subsidisation and spending on education and training then aggregate supply in the long run can also be increased. This would help the government’s of both nations expand their productive capacities to that of pre-war levels and beyond. Therefore the two nations felt it vital to obtain the reparations as soon as possible and began to seize coal from the mining areas of the Ruhr with ease due to the region’s demilitarised nature. However since Germany felt the terms of the treaty were too harsh and the reparations too great the Republic decided to intervene and encouraged the workers in the area to conduct a campaign of ‘passive resistance’ by promising them wages. This policy of passive resistance was successful in winning over the sympathy of the victors and forcing the creation of the Dawes Plan in April 1924 which significantly reduced the debt Germany had to pay. However by this point the German economy was in disarray, leading to the Republic’s leader Gustav Stresemann to order a state of emergency in the nation.

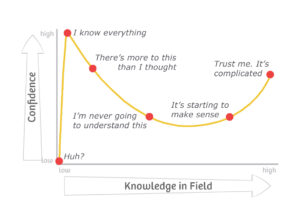

In response to the financial crisis the country now faced as a result of the Ruhr occupation the government decided to print money in order to satisfy the French and Belgium nations. Sounds like a simple yet effective idea at solving Germany’s financial woes right? Sadly this was not to be as the German economists failed to appreciate the effect the printing would have on the value of the currency. This is because the economists did not comprehend the equation MV=PT which explains the quantity theory of money. This is where M represents the money supply of an economy, V represents the velocity (in other words the rate at which money circulates at), P the price levels and T for transactions. Often T is substituted to Y for National income which is to a large extent much easier to measure. But this equation can help prove why an increase in the money supply, and in Weimar Germany’s case the papiermark can cause hyperinflation. This is because Velocity is considered constant in the short-run and Y is also considered fixed as output according to monetarists is inelastic in nature. This means that as M increases so does P, proving how the printing of money can lead to higher price levels and in extreme cases, like Weimar Germany, hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation is defined as monetary inflation occurring at a very high rate. This can clearly be seen in Germany between 1922 and 1923. For example the value of the papiermark in terms of Reichsbank Mark were at 5000 on 2nd December 1922 yet by the 25th July 1923 this figure had reached 1 million. This may seem a ridiculous rate of inflation, which it undoubtedly is, yet the crisis peaked in October 23rd that year when the figure reached 200 billion. By November 1923, the US dollar was worth 4,210,500,000,000 papiermarks. This highlights how volatile markets can become when the policy-makers are not informed of the true economic consequences of their actions.

One of the key effects this economic crisis had on the population was the rapid depreciation of savings and pensions. This was because the rate at which inflation grew was dramatic and banks were simply unable to adjust the value of savings. This lead to widespread tragedy and a serious level of discontent among the populace, something which could be taken advantage of by the Nazis only a few years later. Unsurprisingly during the crisis the growing rate of inflation led to a collapse in each household’s Marginal propensity to save. This left banks without any money to reinvest in industries and small businesses leading to an even swifter decline in the economy. This decreased the level of aggregate demand in the economy and prevented any hopes of economic growth. In this state the economy would not last a few more months let alone years. The only hope for the Germans came in the form of both Revaluation and the Dawes plan.

Following Schact’s promotion to currency commissioner on November 12th 1923, plans were put into place for the revaluation of the currency. Revaluation is defined as the adjustment of the value of a currency in relation to other currencies. In the case of Weimar Germany, this was compared against the dollar index and wholesale price index. This is because the dollar and wholesale price theoretically indicated the true price level in the economy and came in the form of the law on the revaluation of mortgages and other claims of July 1925.

Of course to rule understand the miraculous revival of the economy it is important to evaluate the role of the Dawes Plan. This plan included many points which were designed to restart the German economy and included:

1. The evacuation of foreign troops in the Ruhr

2. The allies would supervise the Reichsbank

3. Germany would be loaned about $200 million primarily through Wall Street bonds

The evacuation of the Ruhr would have helped to restart the countries economy as workers would now be able to engage in the economy through providing factors of production like labour. This could help to slowly improve the nation’s GDP and level of exports. In the case of allied supervision, the Reichsbank would be able to make more informed, rational decision thanks to the provision of a greater amount of information from Allied nations in how to run the economy. This would mean that fewer resources would be wasted and Germany would be able to make its industries more allocatively efficient. Of course the loans from the Dawes Plan would greatly benefit the German Economy as the government would be able to afford to subsidise a large number of firms. This could help make markets more competitive, thereby increasing the welfare of society. This is because competitive markets tend to provide greater quantities of a good or service at a lower price thereby expanding consumer surplus. However there are drawbacks to a primarily competitive markets as a lack of monopoly power typically leads to less dynamic efficiency and investment. Although to evaluate this point it is necessary to acknowledge how in a more competitive market the costs of less dynamic efficiency are arguably outweighed by the benefits of greater innovation.

Perhaps the most obvious consequence of the crisis is that of discontent. This is because the population’s economic future was left in uncertainty as hyperinflation had demonstrated how easily a financial collapse through simple mistakes can lead to dramatic social consequences. However following Schact’s policies and the US bond loans the economy began to stabilise and the years to follow were known as the ‘Goldene Zwanziger’, the golden twenties, as civil unrest began to decrease and the economy began to grow once more. All seemed well yet many people in hindsight can persuasively argue how this was but only an appearance of stability. This is because by the mid 1920s the German economy was all but built on loans from abroad, primarily from the USA.

Of course the 29th of October 1929 has always been considered one of the darkest days in the world economy with the day often being referred to as ‘Black Tuesday’. This was the day of the Wall Street Crash. Unfortunately for Germany this meant that the economy once again dramatically declined as the nation was forced to pay back its loans to the USA and other foreign nations. The German people were therefore discontent once more yet this time there was a political party which could take full advantage of this anger and hatred towards the democratic yet flawed government which presided over the nation. This party was of course the National Socialist German Workers’ Party also known as the Nazi party, whom as a result of the 1932 elections, were able to appoint Adolf Hitler the Chancellor of Germany. This then lead to some of the darkest years of the 21st century with the destruction of war on a whole new level thanks to the latest developments in technology. In this way it is rather ironic that had the USA not intervened and seemingly saved the German Economy, the nation would have had debt on a more manageable scale during the Wall Street Crash and Hitler would have likely lost the election.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.