I’m not happy for Mr Vickers – Mr Hodson

Following Tottenham’s failure to defeat Chelsea last week, Leicester City are, inexplicably, Premier League Champions. To those unversed in such matters: Leicester started the season as 5000-1 underdogs for the title having only narrowly avoided relegation last season.

And how the neutrals are rejoicing; West Brom boss Tony Pulis expressed satisfaction at being able to do a favour fellow Premier League ‘minnows, by holding Tottenham to a draw two weeks ago. Every day a new story details how much some foolhardy Leicester City fan stands to win as a result of a drunken bet made during the preseason. Back in March, an anonymous fan cashed in on a £50 bet for £72,335. With odds of 5000-1 on the ticket, he’d be licking his lips at the prospect of a cool £250,000 had he kept his nerve.

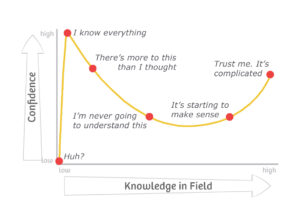

While such stories are manna from heaven for tabloid sports editors and clearly emphasise just how surprising the Foxes’ achievements this season have been, they don’t express the true significance of Leicester’s rise. Ever since Blackburn won the title in 1995, funded by multi-millionaire Jack Walker, no club has been able to break the grip of the ‘big four’: Man Utd, Man City, Arsenal and Chelsea. By doing so, Leicester have apparently renewed faith in the notion that sporting success is about more than foreign investment and global marketing strategies. Who needs eight-figure, marquee signings like Cesc Fabregas or Raheem Sterling when the likes of Jamie Vardy can be found knocking around in England’s much-maligned lower leagues

There is no doubting the quality of Leicester City’s scouting set-up. Perhaps this is no more evident than in the trio of Vardy, Riyad Mahrez and N’golo Kante. Mahrez and Kante were both signed for paltry sums (in premier league terms) from small French clubs, yet both have been named alongside Vardy in the PFA (Professional Footballers’ Association) Team of the Year.

So what’s not to like in this rags-to-riches fairytale, full of good old-fashioned giant killing? Well, let’s start with Leceister’s iconic talisman himself – Jamie Vardy.

Yes it’s remarkable that a man who has spent the majority of his career languishing in non-league football has proven himself to be one of the most potent strikers on the world’s most prestigious domestic stage, and his boundless energy on the pitch only adds to the appeal. Some say Vardy’s is a story fit for a Hollywood script writer. Superficially, perhaps they are right; but the influence of the English football system on Vardy runs deep. He is a thug. See him in interview: he is inarticulate, deadpan and dull. Professional ambitions may have forced Vardy away from formal education at an early age, but that is no excuse for various gross personal shortcomings. Vardy may currently be the toast of the Premier League, but a YouTube video of him targeting racist abuse at a fellow gambler on a casino visit back in August suggested that media attention on Vardy this season would be far less favourable. I don’t care how unlikely the narrative, I’d rather not celebrate such a man’s success. And I hope he doesn’t play for us at the Euros. And if he does, I don’t mind if Germany win. Which they will.

With the likes of Vardy, Wes Morgan and Danny Drinkwater (could you invent a more quotidian name?) at the heart of their team, it’s easy to see why Leicester are seen as the antidote to over-investment and the corporate alienation of the fanbase that has come hand-in-hand with globalisation. One assumes Leicester champion the grass roots development of British players in a time of foreign invasion; of course, this is a simplistic and inaccurate assessment.

On September 28th 2010, I took a small group of staff to see my beloved Norwich City – then in the championship – take on Paulo De Sousa’s Leicester. The former Portugal international’s managerial appointment was big news in the context of the English second-tier and a reflection of the ambitions of a club which had, in August, been taken over by Thai-led consortium Asian Football Investments (AFI), fronted by King Power Group’s Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha. The mighty Canaries thrilled and delighted a near capacity gate that evening, Norwich ran out 4-3 winners, and De Sousa was sacked. Leicester weren’t even doing that badly in the league. Two days later, Sven Goran Eriksson, former England manager, turned up. The narrative is clear: investment, expectation, improvement.

Leicester is not a ‘normal’ English football club. It does not represent victory for the little man or grass roots revolution. Yes, it has achieved remarkable success this season; or, more to the point, it has achieved that success remarkably soon and on a surprising scale. Although recent seasons at the King Power Stadium – and note the capitalist branding at the heart of the club’s identity – have been full of stress, disappointment and heartache for die-hard supporters like our Head of Film and Media, Mr Vickers, Leicester’s rise into the elite of English football should come as no great surprise. Leicester is a well-supported club with proud traditions and a history of moderate success; many would argue it ‘belongs’ in the Premier League. The foreign investment which has seen it secure such ‘fairy-tale’ success in 2015/6 far outstrips all that. Yes, Leicester have recognised what the game is, how it operates, and how to play with the big boys. Yes, their players have shown remarkable discipline in executing their manager Claudio Ranieri’s plans on the field – often against more talented opponents. Yes, it is nice to see the big four’s stranglehold on the Premier League title broken. Am I happy for Mr Vickers? Not particularly.

None of us is capable of looking into a crystal ball and seeing how English football will evolve; had the pundits of 1995 been told 20 years would pass before ‘another Blackburn’ would come along, they may have been dubious. With even bigger money on offer to all Premier League clubs from next season due to massively increased television revenues, and greater financial fair-play penalties being imposed on Europe’s very biggest clubs, the cultural landscape is certainly changing. However, football’s woes run far deeper than inequality between Goliaths like Man Utd and would-be Davids like Norwich City. Football has been a huge part of British culture for over a century and its foundations lie in local identity. We each had a club. Something to belong to. When they won, we felt good; when they didn’t, it was used as an excuse to drown sorrows with fellow fans. What matters is that it was real. You came from Norwich; you supported Norwich; the owners were local and they understood the club. Maybe even a few of the players knew how to drive a tractor.

What saddens me about football today is that predominantly working class men pour huge amounts of time and resources into supporting clubs which, frankly, don’t care about them. While a Newcastle fan earning £25,000 a year spends nearly a fifth of that amount following his team if he wishes to go to all home and away matches, a squad player who might only play a handful of matches for the reserves is pocketing the same amount on a weekly basis.

Do Leicester City really represent an answer to that problem? Is their success one in the eye to the big movers and shakers of the footballing world? No. Leciester have adopted the same strategy for success as many before them; their success only increases the pressure on other clubs to invest further in ill-educated, irresponsible millionaires. The Jamie Vardys of this world now have more money to fritter away at Blackjack. Leicester City is a club whose owners have no connection with the city; every week their fans worship at the alter of the ‘King Power’ corporation. In their moment of greatest success comes their deepest identity crisis – not that you’d guess from the hyperbole that understandably surrounds their recent success.

Meanwhile, we have Delia: and she lives in East Anglia: ‘On the ball, City!’

1 comment