Banned: The Tudor Christmas – Hebe M

As we plunge into full Christmas festivities here at school, it’s hard not to notice how deeply the season shapes the rhythm of our year. When we imagine Christmas, we think of joy: carols, rich food, decorated homes, time with family, and the excitement of gift-giving. But what if none of this existed? What if Christmas itself was banned?

Remarkably, in 1647, this hypothetical scenario became reality. Under the Puritan-dominated Parliament and Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell – Christmas was outlawed.

To Puritans, Christmas was not a holy celebration but a dangerous mix of disorder, superstition, and Catholic influence. They argued that Scripture gave no instruction to celebrate Christ’s birth, and therefore it was an unwarranted, wasteful festival. They felt the season should be devoted to quiet reflection and prayer, not feasting, games, or merriment. Therefore Cromwell allowed Parliament’s legislation to stand. However it’s a common myth that he personally led the charge, as he was not present when the 1647 act was passed. Still, the image of Cromwell as the original “Grinch” has stuck.

Before the Puritans intervened, Christmas in England was a vibrant blend of Christian celebration and much older midwinter customs. The season was linked strongly to the winter solstice on 21 December, marking the end of the agricultural year and the reassuring return of the “life-giving” sun. Traditions included bonfires to “strengthen the unconquered sun”, which was a reminder of just how ancient these rituals were.

The Bible never specifies a date for Christ’s birth. Early Christians celebrated it anywhere between January and September. It wasn’t until the 4th century that Pope Julius I declared 25 December as the date of the Nativity.

Mediaeval and Tudor festivities often included the Feast of Fools, presided over by a “Lord of Misrule” (usually a lively commoner chosen to direct entertainment). Cathedrals such as York, Winchester, and Westminster even appointed a boy bishop from 6 December to 28 December. Although, Henry VIII abolished this tradition, a few churches (including Hereford) still mark it today.

Other traditions included: The Yule Log: chosen from the forest, decorated, and burned throughout the Twelve Days of Christmas, its charred remains were kept for luck.The Twelve Days: began after Christmas, not before and they offered rare rest for agricultural workers until Plough Monday. Mince pies: containing thirteen ingredients, symbolising Christ and the apostles.

The earliest printed collection of carols appeared in 1521, published by Wynkyn de Worde. The word “carol” comes from the Latin caraula and the French carole, both referring to a dance accompanied by song, I think we should consider reinstating this tradition during the carol service this Friday. Festive entertainment also included board games, costumed mumming plays, and even ghost stories told in the long dark evenings. Gifts were traditionally exchanged on New Year’s Day, often between subjects and monarch. Henry VIII once spent the modern equivalent of £400,000 on presents. Homes were decorated with mistletoe, holly, ivy, yew, and laurel, offering colour during the bleak midwinter. While Christmas trees are mostly associated with the Victorians, records show a candle-lit fir tree appearing in London as early as the 15th century—so Prince Albert can’t take all the credit.

Even Father Christmas existed, though Tudor versions wore green and were far more boisterous, sometimes brandishing a club. Luckily, Santa has mellowed considerably since then.

Fasting was common, especially on Christmas Eve, when meat, eggs, and dairy were forbidden. Christmas Day feasts were the grandest among the wealthy. Turkeys which were introduced to England in 1523, became so popular that flocks were walked all the way from Norfolk to London each year. The ultimate showpiece was the Christmas pie: a turkey stuffed with a goose, stuffed with a chicken, stuffed with a partridge, stuffed with a pigeon. (A slightly different take on the “partridge in a pear tree”.) Their version of mulled wine was called Hippocras, heavily spiced and consumed in rather enthusiastic quantities.

Restrictions actually began in 1644, when Parliament ordered Christmas Day to be treated as an ordinary day of work. In 1645, the Directory of Public Worship abolished Christmas, Easter, and Whitsun as feast days. The full ban in 1647 outlawed: feasting and festive gatherings, attending Christmas church services, decorations (including holly and ivy), carols, games, sports, and theatrical performances and closing businesses for the holiday. Soldiers from the New Model Army enforced these laws, breaking up gatherings and confiscating any food that looked too celebratory. Unexpectedly, after carols were specifically outlawed, they remarkably didn’t reappear into tradition until the revival in the Victorian era.

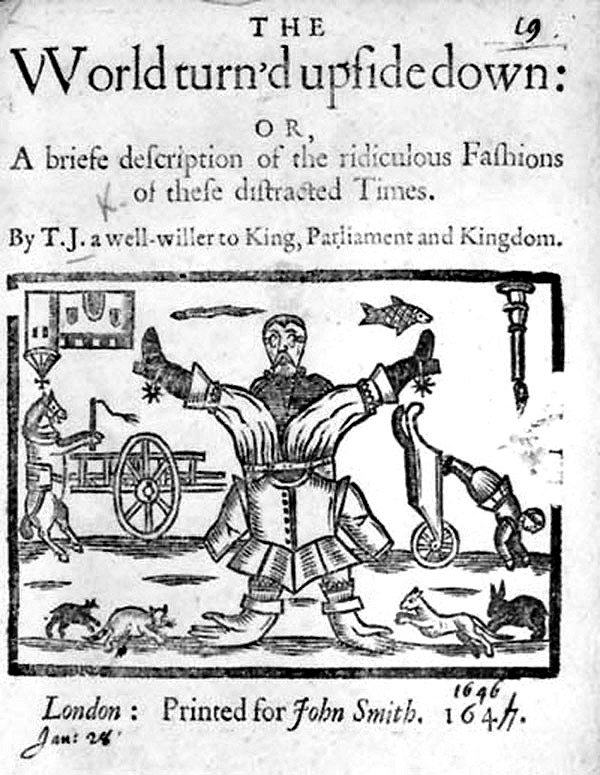

Unsurprisingly, the public did not accept Christmas disappearing quietly. Riots broke out in Kent, Ipswich, Oxford, and other towns. Ballads such as ‘The World Turned Upside Down’ mocked the ban. People protested by: decorating their homes with holly, shouting royalist slogans, holding secret services. Parliament responded by tightening the rules in 1652, imposing fines for attending Christmas worship.

The ban lasted only until the political climate changed. Following Cromwell’s death in 1658 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Christmas was officially reinstated. Traditional celebrations returned with renewed enthusiasm, and in the centuries since, the season has only grown, especially with the commercial boom of the 20th century.

As you celebrate this year, imagine it’s 1660 and Christmas has just been restored after more than a decade in the shadows. Perhaps try a Tudor-style mince pie, dance a carol, or simply enjoy the festivities with a little extra appreciation.

Wishing you all a wonderfully festive Christmas! (one that’s actually legal).

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.