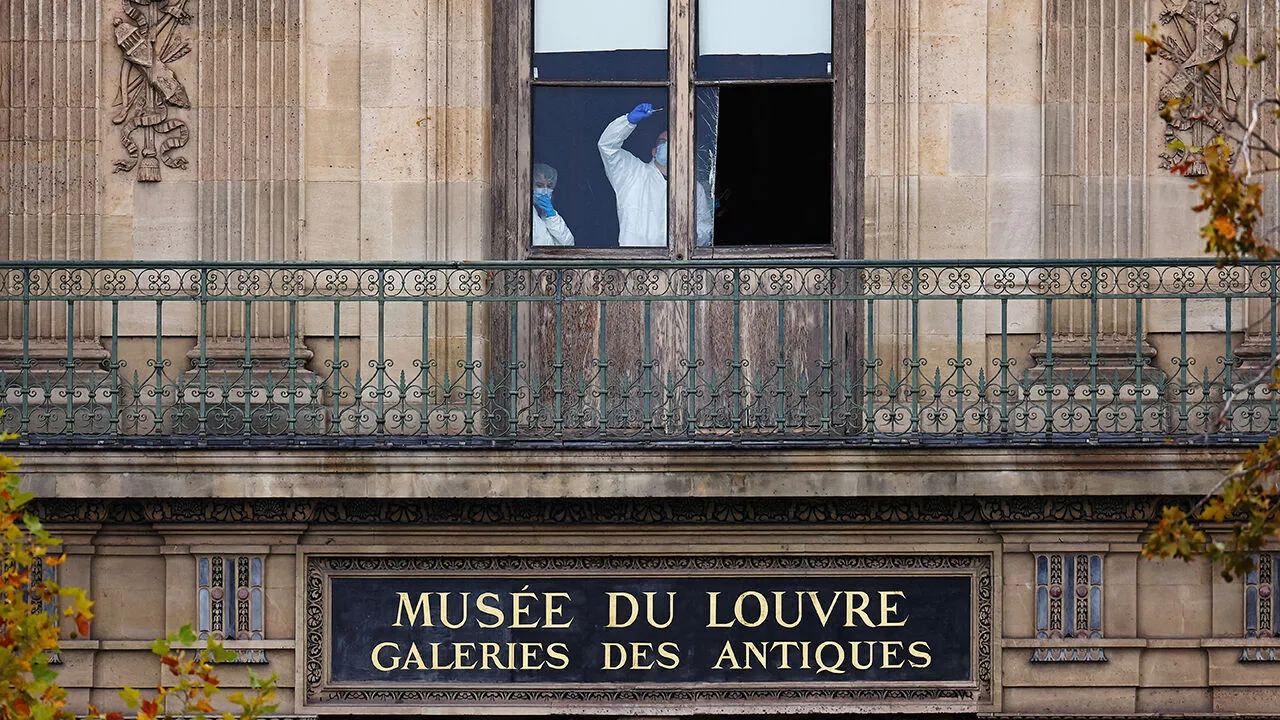

Stealing the Spotlight: The Louvre Heist – Elise L

Shortly after midday on the 19th October, the Louvre museum unexpectedly auditioned for the role of ‘Most Easily Robbed Cultural Institution’ and, to the surprise of absolutely no one on social media, it got the part. Within minutes of the break in – a heist involving a truck-mounted lift, power tools and a seven-minute timer – the media had already turned the event into a stylish blockbuster. The thieves may have escaped with the Crown Jewels, but TikTok, in particular, escaped with something far more valuable: fresh content.

What followed online from the event was not outrage, but enthusiasm. Dramatic edits, – and speculative ‘mastermind theory’ videos appeared alongside articles labelling the thieves as ‘expertly coordinated’ and ‘highly organised’; actions which seemed to grant the event an unearned level of professional admiration. Meanwhile, the genuinely significant detail that only 39% of the museum’s rooms had functioning CCTV at the time, was treated as a footnote, quietly tacked on after paragraphs marvelling at the operation’s ‘precision’.

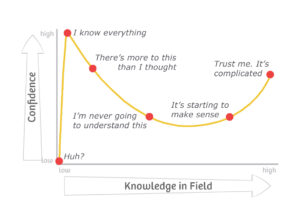

This habit of romanticising crime is not new, but the Louvre heist demonstrates how rapidly it now happens. The modern media environment is driven by virality and instant engagement, encouraging audiences to evaluate events not by their seriousness but by their narrative potential. What is most troubling is that this style of reporting is shifting public understanding: by focusing on the ladders, the tools and the thrill, the seriousness of the crime is minimised. To younger generations especially, the message becomes that cultural heritage is valuable chiefly because it can be stolen, or exciting when endangered, rather than because it represents centuries of history.

In reality, the heist should have prompted a sober discussion about cultural protection at a time where museums face rising threats. Instead, it becomes another piece of viral spectacle. Therefore, the real question becomes this: if we are prepared to turn a cultural crime into content, what else are we prepared to overlook for the sake of a good story?

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.