Why is it that so many of you care so little about languages, even your own? – Miss Wright

Just over a year ago, before the acronym COVID had properly entered the English language, let alone our everyday parlance, I was invited by Mr Johnson to give a lecture to the Studd Society about the evolution of the English language. The sign-up list was long – so long that Mr Johnson booked the Jellicoe. It promised to be a highlight of the Studd Society calendar, so I felt a weight of responsibility. The day arrived, and I set myself up ready to deliver an hour’s lecture that had taken many hours of preparation in my spare time, and of which I was quite proud. In the end, there were only about ten of us in the room, and that included myself and two other staff members. Did I feel deflated? Well, wouldn’t you?

Yet it wasn’t the hours I’d spent on the preparation that upset me; it wasn’t even the notion that pupils couldn’t bear the thought of an hour of listening to me after a very busy day in the toughest half term of the academic year. No, the disappointment went much deeper than that, and I still feel it now, a whole year on. What is it about languages, language acquisition, linguistics and etymology, things that I find so very fascinating, that so many have no apparent interest in whatsoever? I’ve been learning about the development of language since I can remember, and the clues and insights we get about our own language by learning others only adds to the excitement for me.

Languages develop or, more accurately, evolve over time in much the same way as animals and plants evolve, and languages, too, have an evolutionary family tree. That evolution happens over fairly protracted periods of time, so although it is perceptible, a lot of the time we don’t notice it. Someone on my local Nextdoor network was moaning the other day about another member using the term ‘hood’ instead of ‘neighbourhood’. “Why are you using an Americanism when we have a perfectly good word in British English?” he asked. And there’s the rub: as we get older, it’s quite natural for us to become protective of what we grew up believing was the correct mode of expression, we even start to become defensive when people ask questions such as, “Why don’t we just abolish apostrophes?”, but the problem is that we can’t stem the tide: our language will keep on evolving, absorbing, moulding itself to our current existence and technological advances. Of course, there’s a huge contradiction here: as we drive ourselves forward as a species, so we drive our language’s evolution forward, yet there is an inherent desire, especially as we age, to try to resist this forward motion.

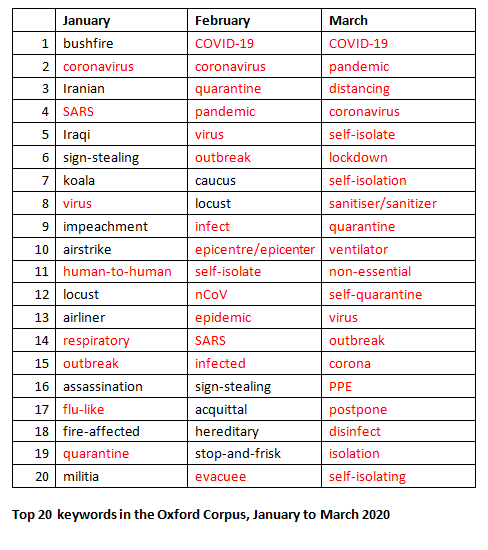

The Oxford English Dictionary employs language scouts whose job it is to monitor the changes in the way we speak and write, and to recommend new words to be included in the dictionary and, you may be surprised to learn, when certain meanings of words can be deprecated because they are no longer part of our active vocabulary and communication. This past year, since we started to realise we had a global pandemic on our hands, we have seen a whole raft of terms, acronyms and new meanings of familiar words enter into our language. A year ago, ‘bubble’ was mostly associated with luxury baths, drinking fizz and, if you were at RHS then, this wonderful online magazine, but now its most common usage is in connection with the numbers of people allowed in a co-habitation group. And then there’s ‘social distancing’. OK, so it had been used in the prophetic film Contagion before last January, but it wasn’t used at almost every verse end as it is now. ‘Corona’ was, a year ago, a well-known brand of beer and a term associated with astronomy and would not then have conjured up the image of illness and loss of life that it does now. In fact, so massive is the influence that 2020 had on our lexicon, the OED nominated 47 Words of the Year for the first time ever, instead of just one: words, acronyms and abbreviations like bushfires, WFH, lockdown, circuit-breaker, Black Lives Matter (or BLM), keyworkers, furlough, remotely, unmute and moonshot are among those at the top of the list.

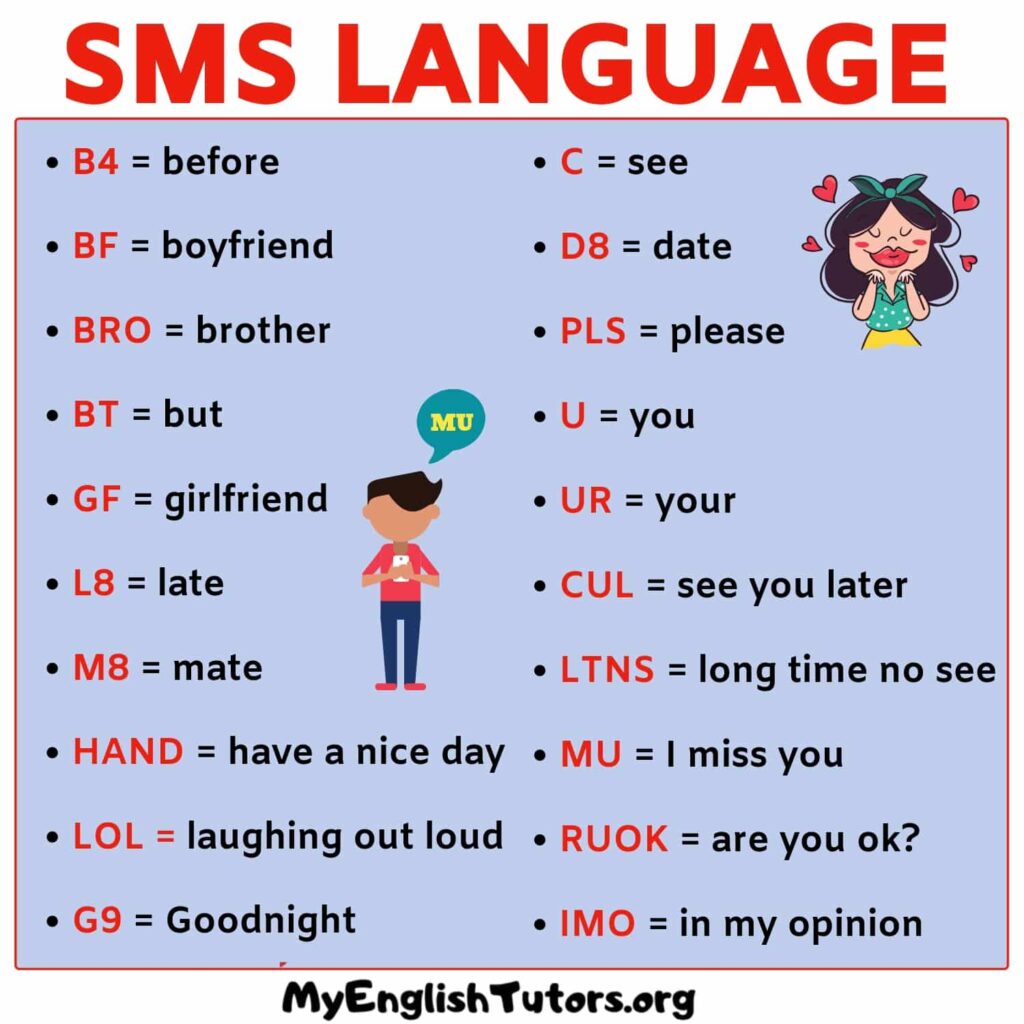

For me, though, the most fascinating thing about language development is this: whilst a language will go on expanding, enriching itself with new terms that are necessary for us to navigate modern life, it will also seek to cleanse itself, shedding anachronisms and trying to simplify itself for a new generation, and text speak is just one example of the way this happens. How many of you have used a LOL or ROFL in some verbal or written communication recently? I know I have. And as new words are invented, so words from other languages are also absorbed: whilst the collective conscience in 2020 sought to right the wrongs of history by toppling statues to figures who’d been associated with the promotion of slavery, we were still happily using words that entered English because of our British penchant for land-grabbing (otherwise known as colonialism), words like shampoo, juggernaut, yoga, bandana, cot, guru, avatar and loot, all of which came to these shores because of our former empire in India and the Raj.

So a plea from me to you as I enter the final 100 days of my teaching career with dwindling opportunities to try to influence you: be aware of what you write and say, ask yourself where it came from, wonder why we say it in that way and what it was that made English ‘invent’ it or adopt it in the first place. Language is a wonderful thing: you shape it, history influences it, technology drives it and humanity needs it. Don’t take it for granted, because it is a living thing, just like you and me. It’s a part of you and it will define you, just as it defined your ancestors, and the reason that you’d be unable to have a conversation with your distant ancestors, despite sharing their DNA and looking very much like them, is not because they couldn’t communicate with each other, it’s because the language they spoke has gone, shifted and shaped over time to become your language. Be proud of it, learn to love it and know it as well as you know (or should know) your family and their history. Language is beautiful, complex and beguiling, but it’s fickle, too: it will not last forever in its current form as it shape-shifts its way forward. Don’t be ignorant of it and its roots, because mastering it will make you more powerful than you can ever imagine.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.