The Value Of Gaming – Mr Mackenzie

SHOULD WE REASSESS THE EDUCATIONAL VALUE OF GAMING?

Hamish Mackenzie – Head of Digital Strategy and Learning – Royal Hospital School

SOURCE Lhttps://www.pexels.com/photo/battleroyale-fortnite-1158215/

THE ISSUE

The global games industry is worth more than £137 billion and one of the UK’s most successful creative exports. It is estimated that there are in excess of 2.3 billion gamers worldwide, with an ever-increasing number participating on mobile devices.

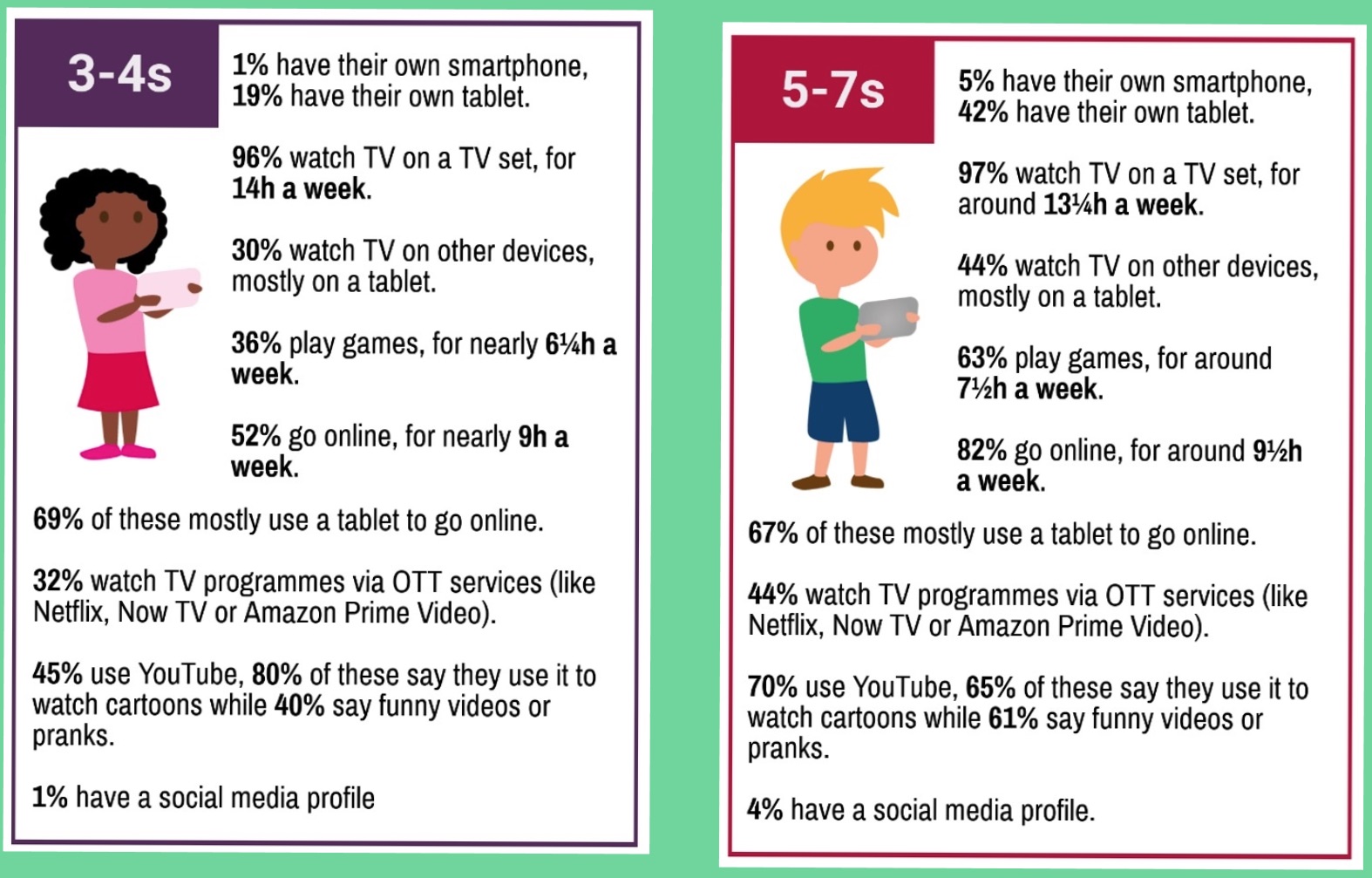

Much of the success of this industry is down to device proliferation in the youth market over the past 10 years and the drive towards mobile devices as the preferred platform. The recent Ofcom children and parents use and attitudes report showed that children are plugging in to connected apps and platforms at an ever-younger age.

(Source graphic: Ofcom Children and parents use and attitudes report 2018 – Page 3)

The trend in the Ofcom report is the growth in the percentage of children who play games as well as the increasing average time spent on game play as children get older , and the preference of tablet and mobile devices. The report also highlights a large increase in the number of children who are taking a mobile or tablet to bed with them – a worrying trend from a safeguarding and health perspective.

The youth gaming market is ferociously competitive with companies recognising the value of a young customers and the potential to build brand loyalty. Big game launches now command similar budgets, marketing campaigns and press interest as A-list Hollywood films. Increasingly, the most profitable titles are free to use and leverage revenue once players are engaged within the platform. The industry-leader, Fortnite, grossed a staggering $2.4 billion in 2018 (SuperData). Fortnite’s revenue is generated by selling in-game ‘skins’ and microtransactions, alongside selling ‘Battle Pass’ updates that offer players new challenges.

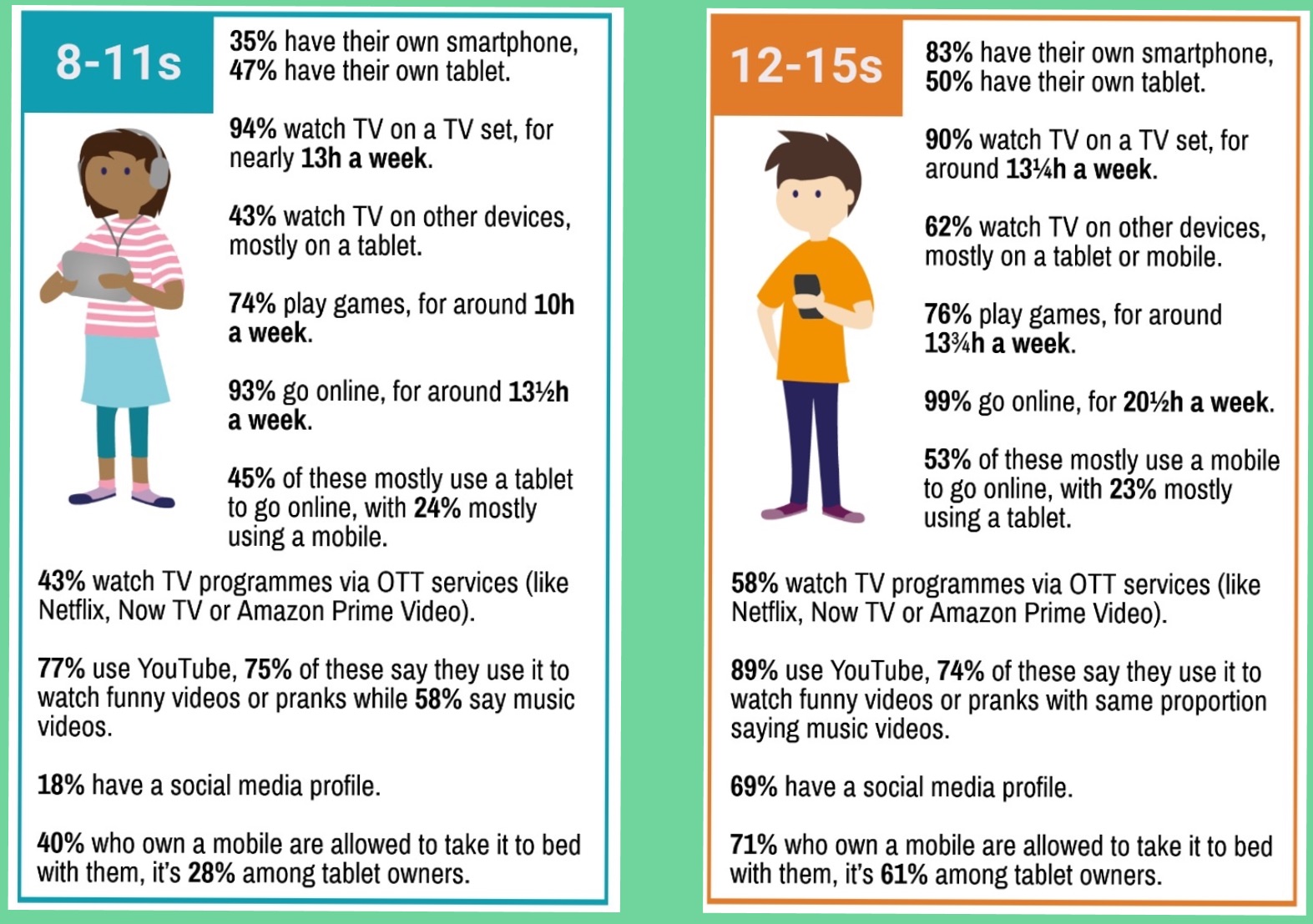

Gaming analytics organisation Newzoo provide a useful breakdown of the market, revealing the scale and relative sub-sector sizes.

Source: https://venturebeat.com/2018/04/30/newzoo-global-games-expected-to-hit-180-1-billion-in-revenues-2021/

Whilst device proliferation and younger age-engagement may explain this growth, there are many parents and teachers who are wary of the addictive nature of the platforms and the behaviours that they can drive.

The current game in vogue at the Royal Hospital School, a coeducational boarding and day school for 11 to 18 year olds in Suffolk, is Apex Legends. The extraordinary popularity for new game titles is shown by the global audience and instant engagement they command – Apex Legends had over 2.5 million unique users and over 600,000 concurrent users on the first day after release. This is the latest in a run of familiar battle-royale genre games that include Fortnite and Clash of Clans.

As educators and parents, it feels like we have little power in comparison with the lure of these games. The games are addictive by design and use sophisticated techniques; they exploit needs within the human psyche. Increasingly subtle methods are used to drive engagement and maximise player attention on a given platform.

The attention-grabbing mechanisms of these games do not automatically equate to game studios being motivated by the corruption of youth and monopolisation of the market. Games are designed to be fun – the skill of the designers is to provide an engaging, challenging and worthwhile experience that will keep users hooked and returning for their dopamine hits.

Proponents of video games, such as Jordan Shapiro in his book The New Childhood (2019),espouse the educational value and social development possibilities of video games. He argues that far from being nefarious, video games share many characteristics with great teachers. Shapiro suggests players have to follow a systematic approach in order to progress within games, in much the same way that students acquire a new language. Games are full of interconnected and subtle rules that players must master in order to progress.He argues that video games are rigorous (not too hard or easy, players are kept in the zone of proximal development), responsive (instant feedback is available on why strategies fail), reflective (meta-cognition opportunities are continually available as players can separate themselves and their thinking from the actions of a player within a game) and real (games are kinesthetic and experiential in their nature). Players learn by doing, exploring and engaging in trial and error. Games are by their nature personalised and differentiated – a much-cited goal of 21st century education.

There are many commentators within the press and education contributing to the polarised debate around the impact that screen time and game play is having on teenagers and their personal and social development. Whilst opinion and rhetoric vary enormously on the value gaming is having on young people, the evidence is far from clear.

THE EVIDENCE

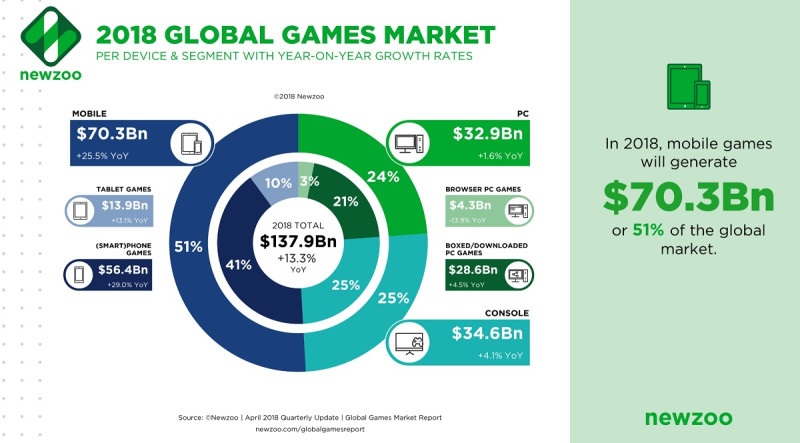

In February 2019 the Chief Medical Officers of GB and Ireland published guidelines on screen time and the impact on young people. Far from being decisive, the advice seems to reflect the common-sense values that children need sleep and to maintain a balance between online and offline worlds as intensive online engagement almost leads to a sedentary lifestyle. The official advice recommends:

– A precautionary approach should be taken, balancing the benefits and negative effects of screens

– No screens before bed and to leave screens outside of the bedroom

– Screen-free meal times and engage in face-to-face conversations giving full attention

– Take a break every 2 hours

It also recognised the importance of agreed boundaries; adults leading by example and the need to be able to engage in open and honest discussion.

Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/777026/UK_CMO_commentary_on_screentime_and_social_media_map_of_reviews.pdf Page 10

Success is most likely to occur when a balance is found between online and offline behaviour and young people self-regulate their consumption – they develop a self-awareness. The other universally reconginised good advice is to ensure that young people have safetynet of trusted peers or adults to talk to and who recognise when their behaviours are changing.

At the Royal Hospital School, we try to avoid the online / offline distinction as we recognise that there are many valuable social and cognitive benefits in integrating online and offline experiences. Whilst it is easy to retreat towards the on/off mentality, it is a false binary. Children can grow or be diminished in both spaces. Many of the development benefits we would want children to learn offline, are being taught in games. Rituals, boundaries, unspoken rules, problem solving, decision making are all apparent – strengthening important neural pathways around skills that are needed in the real offline world. Steven Spielberg’s latest feature film, ‘Ready Player 1’ explores some of these ideas, I often use it as a metaphor when speaking to our sixth form students on the the relative importance of each world within their lives.

In a recent CPD session with Chartered Clinical Psychologist, Dr Bettina Hohnen, we were walked through some of the science of the adolescent brain development. Dr Hohnen highlighted the importance to the teenage brain of developing a sense of self and building independent friendship networks. She also highlighted the enhanced neurological rewards of risk-taking behaviours. It is clear that within game environments there are ample opportunities to exercise these developmental requirements.

USING GAMING POSITIVELY WITHIN SCHOOLS

All schools strive to deliver a personalised, creative and differentiated learning experience where feedback is regular and progress can be measured. Games (and the new digital iterations of them) are a key tool in a teacher’s arsenal.

As a tool for assessing learning, games are fantastic at engaging and generating data on student understanding. Any teacher who has experimented with quizzing apps such as Kahoot, Quizziz, or Memrize will testify to the enjoyment gained from playing them and the instant data the teacher receives on the relative progress of the group.

Google have developed a free platform game ‘Be Internet Legends’. The game rewards players for responsible behaviour, conditioning them in areas such as data protection, being respectful, thinking before posting, being kind online, blocking and reporting cyberbullies. I would argue that it is a far more effective tool for teaching KS2+3 digital citizenship and online safety than the traditional teacher-expert assembly or lesson.

In 2014 Microsoft acquired Minecraft for $2.5billion and has since offered it free to schools as part of their education package. When combined with Skype, players can immerse themselves in real-time collaborative adventures where cooperation, teamwork and problem solving are rewarded. These are surely skills that we wish to engender in our students rather than block, obstruct or dismiss simply as ‘screen time’.

Apple has developed its own coding platform with associated learning resources. It is a gamified environment that gives students the opportunity to progress from simple platform game tasks that involve coding basic functions and algorithms, to advanced coding and app development. The resources and platform are fun and engaging. We provide curriculum space for KS3 students to progress through the early stages of Swift Playgrounds, giving them time to solve problems and learn a programming language that has real value in the 21st century jobs market.

It is against these benefits that schools and educators need to consider the value they place on gaming as a tool for progression given the counter arguments below.

LEGITIMATE CONCERNS

Adolescent mental health is a huge concern to all involved in education. Each tragic story of youth suicide makes us reassess our approach and ask the question, could this happen to one of my students? The tide of teenage self-harm seems to be of epidemic proportion and traditional school or parental approaches to the these issues seem to have little impact in an ever-more fragmented world where online-influencers, Instagram celebrities and closed messaging groups have ever more weight in forming young peoples’ opinions and sense of reality. Whilst many of these issues are attributable to social media rather than specifically gaming, it would be remiss not to consider the online safety risks of gaming.

The audience for games is predominantly (but not exclusively) teenage boys. Concerns include; grooming and exploitation, exposure to adult themes, unregulated screen time, promotion of gambling and detachment from offline reality;

Perhaps the most high-profile case to consider is the murder of Break Bednar, a 14 year old gamer who fell victim to an online groomer. Breck’s case is shocking as many of the actions that his mother took when she realised there was an issue would be recognised as best practice, highlighting the fact that it could happen to any of our children. His mother, Lorin LaFave, has set up a foundation in her son’s name – ‘The Break Foundation’ and she works tirelessly on education programs to train police, teachers, health practitioners, safeguarding leads and parents in order to empower students to make safe choices online. I would encourage anyone involved in this area to watch the film ‘Breck’s Last Game’ available via the Breck Foundation.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PARENTS

Parents look to schools for guidance on these issues and to find out whether their child’s experience is normal. Parenting styles and boundaries vary considerably, and it is not surprising that very different approaches are evident. PEGI age ratings provide parents with useful guidance but a discussion with any KS1 or KS2 class will show the knowledge younger pupils have to titles such as Grand Theft Auto and Fortnite, often as a result of exposure via older siblings or with the consent of a parent.

Parental engagement can be a challenge. At the Royal Hospital School, we have adopted an approach that uses social media to communicate on digital issues alongside traditional methods of inviting parents to workshops and regularly sending out useful resources. We subscribe to Digital Parenting magazine from Parentzone and send physical copies home with students. Perhaps our most effective channel of communication are the regular tweets and infographics that we send out based upon particular games and trends that we are noticing in school. Social media channels also allow us to share good practice from classroom sessions and respond to press reports or news items about online gaming that may raise concerns with our parents. We also disseminate some of the free resources available from National Online Safety such as the weekly #wakeupwednesdays graphics.

EXTERNAL INPUT

In 2018 HMC engaged Digital Awareness UK to make a short film and associated learning resources, looking at the issue of tech control (search: Tech Control 2). The film follows three young people and relationship with technology. The film’s message is that technology and gaming can be hugely beneficial if used effectively. All of the characters used the film to positively encourage self-regulation and demonstrate how they personally took control of their online habits and exposure. Two of these young people were pupils at the Royal Hospital School.

At the Royal Hospital School we promote youth voice and provide multiple opportunities for our young people to shape policy and controls. We do this via our eCouncil, Digital Leaders programme and by making space in the curriculum. Our Digital Leaders create regular educational web clips and lead on relevant topics wherever possible.

Successful educational approaches require schools to move beyond the ‘games sit in computing / ICT’ world towards ‘games are part of the natural development of children’ stance. The recent Education for a Connected World framework published by the UK Council for Child Internet Safety (UKCIS) provides a structured curriculum from early years through to 18. It carries 8 key strands through the framework and provides a solid foundation for equipping young people with the skills to thrive in their digital lives.

SCHOOL CONTROLS AND APPROACHES

When considering the concerns outlined above, it is tempting to lock school systems down and prevent access to games, but this would negate the many positives that gaming can offer. There is a balance to be struck. At the Royal Hospital School, we have found that banning games and tightening our Mobile Device Management system perversely led to students watching other gamers play on YouTube, raising the profile of online influencers and returning them to passive consumers of media. However, we also recognise that opening our system to all games would present a huge distraction to our learners and negatively impact outcomes.

We use tools such as Apple Classroom to ensure teachers have visibility of pupil’s screens in lessons and offer a whitelist of approved games. We continue to engage with external consultants, with successful relationships developing with Digital Awareness UK and the South West Grid for Learning. These external experts, along with our digital curriculum, allow us to educate our students on a broad range of issues such as digital distraction, FOMO, sexting and game addiction.

IN SUMMARY

The genie is not going back in the bottle. Device proliferation and the Internet of things (IoT) mean that young people are living increasingly connected and interconnected lives where game play is a central component. Traditional approaches to education, parenting and safety are being challenged by disruptive technologies and networks.

I believe the challenge role of parents and educators is to recognise the opportunities these changes bring in terms of social and educational development, whilst minimising the exposure to risks. Just as we would not send a Year 7 group off in to a city for a field trip without adult supervision, we should provide the parameters and structure to allow young people to explore virtual worlds within a set of boundaries and with the consent of adults.

A balance must be found between the physical and network safeguards that prevent access and sees games as the problem, towards effectively engaging young people with positive conversations and curiosity about their online lives. As educators we must try to disassociate from the mentality that games are a waste of time as they can form an real and valuable part in development of the young people in our care.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.