Languages do not stop changing – Flo Balmer

Flo gives a compelling insight into the intricacies of language, which is constantly adapting and whether this change needs to be controlled.

Languages do not stop changing. Is this a good or a bad thing? Give examples of language change (from English and/or any from other languages), discuss the various processes through which language change takes place and evaluate critically two propositions (A) that language change is a good or a bad thing, and (B) that we should try to control the rate of change (stop it, speed it up).

Every single language has evolved through a series of mechanisms and under the influence of other languages to assume its current form. Although a correct grammatical version of each language exists, in reality this is impossible to confirm, as language is a vehicle of communication the primary function of which is to enable us to convey internal ideas and recreate experience in a communal environment, meaning that it is constantly undergoing change. Considering that language itself is shaped by every linguistic encounter that takes place in its speech community, the rate at which the process of language change occurs will inevitably vary from case to case. Language change may awaken a stimulation of creativity and provide social advancement and a solution to an issue of communication within the language,[1] thereby lies a convincing argument for its activation. Yet this is at the expense of continual dispute, confusion and the conceivable loss of the heritage and culture of its discourse community.

Due to the diverse influences to which language is subjected, there are a variety of processes by which it may change. Firstly, it is crucial to recognise that language is dependent on the actions and movements of humankind and can be manipulated to suit a speaker’s needs. A development may derive from an obligation to fill a gap within the language. Therefore, change may occur when someone notices and thus attempts to solve an inconvenient deficiency in their language. The vocabulary of a language expands each time someone creates a nonce word, like fluddle,[2] or constructs a word with longer lasting effect, for example Ms, which was created to dispel the difficulty of knowing when to use Mrs or Miss[3]. Sheer linguistic creativity may instigate change; Shakespeare was renowned for several coinages and some have even been integrated into the modern English Language, such as accommodation, laughable and eventful.[4]

Language may change due to internal factors, independent of sociolinguistic pressure, leading to an alteration caused by a structural requirement in the language. One such example is the use of the weak verb pattern in forming the past tense in the English language.[5] This leaves the stem untouched and involves one type of suffix, removing the risk of incorrect stem alteration and many unpredictable verb forms. The weak verb pattern is formed more readily by a child in first language acquisition, and such over-extension has made this the popular form, leading to the removal of the alternative, more complex form. This is analogy, the regularisation of unusual paradigms, which functions by removing one marked element and thus provoking further change which results in a type of snowball effect[6]. Language change is an epiphenomenon,[7] it is not the intention of the speakers to induce it, but it can occur when an individual spontaneously shortens or lengthens a word or uses it within a new context. Like in the case of the Great Vowel Shift,[8] causing English to redirect towards Latin pronunciation due to its status as the ‘queen of tongues’,[9] such change may be seen as more fashionable or convenient by other speakers, leading to its diffusion through the speech community by exaggeration and hypercorrection.[10] This was illustrated in French through the development of the nasal vowel, which acted as an indicator of upper class in society. This probably accounts for the unusual stress on this sound in modern French, as lower classes would have modelled their own speech accordingly at the time of transmission.[11]

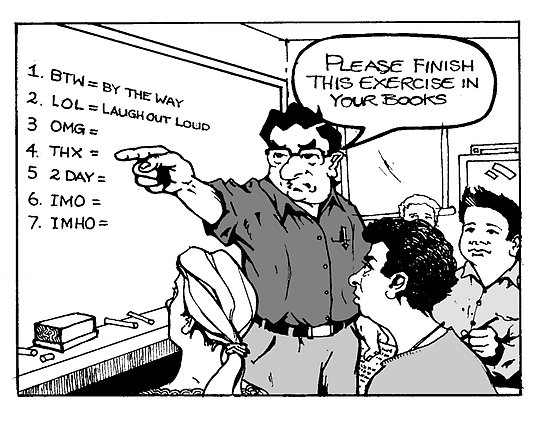

The grammar of a language is less responsive to external influence, as it is the basis of which a language is formed. Change in grammar may be adopted by a speech community when they recognise its comparative ease. These changes normally occur when one speaker creates an irregularity, which is generalised to other words until the critical mass has changed, engendering the remaining words to join the majority.[12] Grammaticalisation implies the transformation of a full lexical unit into grammatical markers.[13] For example, in Old English, the word dōm meant judgement or condition but has now lost its status as a lexical item to become suffix, such as part of kingdom.[14] Such gradual changes, implemented slowly through a community via copying and language contact, may result in semi-lexical words, clitics or inflections, the latter being a permanent loss of independence and retention of grammatical meaning only, which was the fate of dōm. Lexicalisation is the act of placing two words together and treating them as one lexical unit, like girlfriend or gingerbread,[15] so that it becomes recognised as such by all of the speech community. Alternatively, derivation may occur, which is the addition or removal of affixes to words, meaning adjective and noun forms exist, such as adding al to culture, creating cultural.[16] The reverse of this process is backformation;[17] one such example being that the verb diagnose was derived from diagnosis. Due to our obsessive need to ‘conveni-ize’ our language, we often stylistically extract an arbitrary proportion of a word to invent a new lexical unit of identical meaning, such as gymnasium universally being termed gym.[18] Due to popular usage and the disconnection with their parent lexemes, the results of clipping, blending and making acronyms are not merely degraded to abbreviations. All these processes may occur through (particularly younger) individuals copying and modelling features of speech from others, because they recognise the social prestige attached to the change.[19]

Many individuals find the question of language change one of high controversy, raging against the domination of foreign tongues, and such altercations tend to focus on external change. Following globalisation and the birth of the internet, the case of geographical isolation is extremely rare and there is more intercommunication between nations,[20] thus this increased language contact frequently activates change. By multilingual speakers introducing new words into a language, change occurs through borrowing[21] and is often the product of an absence of the entity that the word denotes in the receiving language. Yoga entered the English language in 1818, but there was no way to translate it because the discipline was not previously practised there, hence it was directly imported.[22] Unsurprisingly, it is common for words to be borrowed more frequently in a community where many speakers are multilingual and thus facilitate this transaction. In Canada, both French and English are officially recognised and commonly mixed in conversation, leading to grammatical features or words such as chauffeur and croquet being transported into English, which in turn has proffered the likes of internet and weekend. The success of this procedure depends on community size, for any change in language depends on whether enough speakers prefer and embrace the new version, so purposely discard the old which has continued to coexist. It must be repeated enough for irregularities to become conventionalised and overcome the threshold of rarity.[23]

Speculation upon the nature of language change tends to produce negative results and sentiments of patriotic ill feeling towards the degradation of language and the extrapolation of fearing that a mother tongue may alter unrecognisably. However, one must note that there are considerable advantages to linguistic evolution and development to a speech community, due to the position of language as an instrument of communication. It is a self-regulating process, accommodating and compliant to its speakers on whom it is dependent. Change does not always successfully dominate a language, for example several new dialects of English immerged when the British colonised America, but the English accent has still survived and we continue to resist American pronunciation and spelling. As depicted by Erin McKean[24], every new word is a chance to express ideas and, essentially, to convey meaning. With the rapid expansion of new technology, linguistic change is a positive reaction as it allows this advancement to be communicated within society. Suzanne Talhouk[25] asserts that Arabic does not suit the needs of its people, seeing that it is not a language of science nor the workplace, and thus she stresses the need for evolution in order to permit its speakers to keep up with other communities. Mark Pagel[26] identifies language change as the key to our betterment; the function allowing humans to acquire a superior state and to collaborate, communicate and consequently advance. Perpetual change has led to enhanced sophistication in language systems, moving from a pidgin state to complex structures and broad vocabulary. Following substantial change, there would be fewer issues of miscommunication, plus finance and time could be saved on the translation and interpretation process, which annually costs the EU over one billion euros.[27] One could therefore conclude that it is a positive process.

Conversely, the fear of the destruction of a language due to uncontrollable change is a main argument of the opposing case. As language expresses cultural conventions, concepts and particularities, each language death is a cultural tragedy as these may also be lost in the process; especially in small indigenous communities like the Aborigines, who lost tradition, lifestyle and culture through the death of 100 of their 250 original languages following colonisation.[28] Lexical borrowing is a key component in change, but, in its extremity, leads to language suicide or murder.[29] Borrowing can generate confusion when accomplished erroneously, since the meaning of words may alter, for example cafeteria denotes a coffee shop in Spanish, yet a canteen in English.[30] The standardisation process is crucial in empowering the transmission of language and with language constantly undergoing lexical and semantic revolutions, this provokes an endless search for mastery that can never be obtained. Furthermore, it is functionally disadvantageous for language to alter with constant rhythm as this is hindering communication between social groups,[31] as one initiates change at a faster pace and, due to lack of intimacy, these alterations are not disseminated. This has been the unfortunate experience of Tok Pisin speakers, where the urban and rural communities now struggle to converse with each other.[32] Particularly amongst the adolescent community where most experimentation and variation occurs, the primary cause is usually inertia. Hence, the full potential of language is not always met and some beautiful and lyrical language is only used in written language, and thus this incessant change is viewed negatively.

Owing to the individualistic style of language change and the external influences weighing upon it, measuring the rate of change is an arduous task. However, it may serve as an indicator in deciding whether language change is a good or a bad thing. The rate depends on the size, location and social mobility of the speech community and the language regulations. To alter the rate, one must control these conditions and use mechanisms such as literature and media to influence the speakers, yet the complexity of this is naturally immense. Language change can be measured in an S curve,[33] but it is already approaching the last bend at the time of recognition, thus it is difficult to reverse. Although perhaps futile, impeding change may have considerable advantages, preserving a language in its present form in the aim of linguistic harmony, security and heritage. In a desperate attempt at preservation, the Académie française attempts to command the French language through establishing a dictionary, although the latest attempt was started in 1930 and they are only up to the letter P;[34] the language has already dramatically advanced. Slowing the rate of language could prevent confusion, the mixing of words whose context has since changed, such as gay now meaning homosexual rather than merry, which in turn could improve inter-generational communication. This prescriptivist view continues in the same vein towards slang, naming language change as the culprit for an increase in the disability to converge and diverge language appropriately[35], hence it is necessary to slow down this deterioration to preserve the art of skilful communication. People can react very sensitively to language change; in Quebec, fines of up to $10,000 have been charged by the 400 ‘language police’ following the law against English influence by the Commission de Surveillance de la Langue Française.[36]

Contrarily, inducing language change and promoting alterations of lexical and grammatical rules may also improve a speaker’s experience. The English language comprises of a number of sexist terms, such as mankind, housewife and, grammatically, the use of his as the general possessive pronoun.[37] The removal of such innate sexisms, such as the progression in unofficial language to their, is in keeping with the current society and demonstrates the necessity that language adapts. Additionally, subtle changes, such as standardising grammar, would dispel irregularities and generate less mistakes in first and second language acquisition, as it would be easier to learn with the removal of complications over pronunciation,[38] for example the kn in the word knife. Quickening the rate may also suit social needs; the Japanese language was modernised in 1946 by limiting the number of the old kanji characters in an effort to simplify the vast range of complex characters, which was seen as a factor in unification and modernisation.[39] The invention of the printing press accelerated language change, because it made it much easier to regulate and standardise the characters used. It also eliminated several irregularities and generated the appointment of a Schriftsprache of the English language,[40] which further demonstrates that to attain linguistic harmony and clarity, increasing the rate of language change is beneficial. If language did not change, there would be no new words or lexical creativity and people would be using an archaic system not designed for modern usage, which would obstruct communication. Developments may soothe aggravating nuances, such as the removal of exceptions, like h in some dialects of English, leading to language change becoming a solution rather than the root of the issue.[41]

In conclusion, language is detailed social technology that will continue to change inevitably, due to its position as a medium of communication. Proclaiming these changes to be signs of progress or decay, therapeutic or disruptive, creative or disorientating, vital or obstructive, is nearly always futile[42]. Language will continue to develop through hypercorrection, conscious exaggeration and language contact according to the requirements of its speakers, for ease of communication, social factors or to provide a means of expression, despite of complaints in either direction. Dictating its rate may have its relative merits, but it will not alter at an immoderate pace as ‘the arbitrariness of language ensures the non-arbitrariness of change’.[43] Yet in a globalised world where it has the capacity to occur more than ever before, language change must be embraced.

[1] McMahon, 1994, p138

[2] Crystal, 1995, p132

[3] Trask, 1994, p1

[4] Crystal, 1995, p63

[5] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/

[6] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/ – The force of analogy

[7] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/ – Nature of language change

[8] https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/english-changing

[9] Aitchison, 2013, p10

[10] Aitchison, 2013, p58

[11] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/ – Motivation for change.

[12] Hickey, 2003, p55

[13] https://web.stanford.edu/~traugott/resources/TraugottLuraghiProofs.pdf

[14] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/HE_Grammaticalisation.htm

[15] Trask, 1994, p19

[16] Trask, 1994, p20

[17] https://www.thoughtco.com/back-formation-words-1689154

[18] https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/english-changing

[19] Aitchison, 2013, p32

[20] www.philadelphia.edu.jo/academics/knofal/uploads/Language%20Choice.ppt

[21] McMahon, 1994, p200

[22] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-26014925

[23] https://www.uni-due.de/SHE/index.html – Transmission of language change

[24] https://www.ted.com/talks/erin_mckean_go_ahead_make_up_new_words

[25] https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_talhouk_don_t_kill_your_language?language=en

[26] https://www.ted.com/talks/mark_pagel_how_language_transformed_humanity

[27] https://www.ted.com/talks/mark_pagel_how_language_transformed_humanity/transcript?language=en

[28] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-11-19/collins-aboriginal-language-decline/4378376

[29] McMahon, 1994, p287

[30] Trask, 1994, p13

[31] https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2003/ling001/language_change.html

[32] Aitchison, 2013, p240

[33] Hickey, 2003, p54

[34] https://www.ted.com/talks/steven_pinker_on_language_and_thought

[35] https://mentalfreedomblog.wordpress.com/2015/10/22/language-change-good-or-bad/

[36] Bryson, 1990, p32

[37] Trask, 1994, p75

[38] Trask, 1994, p76

[39] https://www.jstor.org/stable/2384796?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_language

[40] https://rafangel.wordpress.com/2005/04/23/meet-my-divas/

[41] Aitchison, 2013, p234-5

[42] Trask, 1994, p73

[43] McMahon, 1994, p6

CWD – Y11

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.