Multilingualism Matters – Flo Balmer

Being part of an international community at RHS constantly exposes us to foreign languages, and consequently a multitude of different cultures. Whether or not each of us personally chooses to embrace language learning, and enrich our own experiences by doing so, it is irrefutable that the benefits of being multilingual are incalculable and the reluctance that many Anglophones show towards learning another language seems quite illogical.

Despite the rather depressing fact that 66% of British people are monolingual and the majority of the bilingual community are immigrants, various studies have proven that the advantages of multilingualism spread far beyond the spheres of linguistic knowledge. The language we speak is the lens through which we see the world and the means by which we interact with our surroundings. For example, it is said that some ancient civilisations had a grammar system which meant that they perceived time differently to the modern English speaker. Rather than regarding time as the stationary object through which we move forwards, leaving the past behind and heading towards the future as we do in English, their language structure meant that they observed time as overtaking from behind as the moving factor whilst they stood still. What can be deduced from this, and several other examples of this type, is that our language affects the way we think. Therefore if you are bilingual, rather than looking at the world in one way, you are actually viewing it in a variety of ways, thus broadening your mind set and developing alternative ways of thinking and processing information. It has been proven that this effects creative ability and greatly improves critical thinking skills, because rather than seeing the world in black and white, everything becomes colourful, multidimensional.

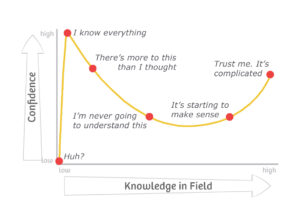

Traditionally, popular opinion dictated that speaking more than one language was more of a hindrance than a help. Early studies showed that it hampered academic ability and overloaded the brain as it attempted to deal and process the different grammar structures, vocabulary and the nuances of idiomatic meaning between languages, slowing down cognitive functions. However, whilst this may be partly true, since within the bilingual brain the two language systems are constantly active, and the correct word must therefore be subconsciously selected at all times, it seems that managing languages in the brain can serve to keep it active and far more stimulated than the monolingual alternative.

Bilingual people have a heightened ability to monitor their environment and respond to it. Consider driving a car: one must unceasingly be on guard and ready to respond to change. This is very similar to the everyday experience of the bilingual person, for often they are communicating in one language with one person, whilst hearing and understanding another conversation in a different language in the background and simultaneously trying to filter out the words of another, unknown language, from yet another conversation. However, rather than finding this a constant struggle, their brains have grown accustomed to this and they have adapted to focusing and switching between linguistic systems quickly and with ease. The part of the brain that manages this is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Located in the frontal lobe, it allows us to focus on one task while blocking out competing information and enables us to switch our focus of attention quickly with little confusion. Another effect of this is an improved aptitude in communicating effectively and polyglots are more perceptive and aware of their surroundings.

Economist Keith Chen recently delivered a fascinating TED talk about how our language can affect our ability to save money, drawing on the theory that the language we speak affects how we think, and thus how we perform professionally. One estimate even puts the value of knowing a second language at up to £100,000 over 40 years. This idea is applicable to multilingual people, by speaking more languages, we expose ourselves to more ideas and the language can actually enable us to explore more creatively as the brain adapts to the new linguistic structure. Numerous studies have provided evidence for the theory that bilingual people have better memories and faster thinking systems. Unsurprisingly, the health benefits of multilingualism are now increasingly recognised. In a recent study of 600 stroke survivors, cognitive recovery was twice as likely for bilinguals as for monolinguals and bilingualism has even been shown to slow down the onset of Alzheimer’s and brain ageing, due to the increased daily mental activity.

Yet with the simultaneous growth of super languages and globalisation, is the number of bilingual people fated to decrease? Approximately 70% of the world is currently multilingual, but with the present rate of the loss of one language a fortnight, experts are predicting that we will lose half of the languages in the world by the end of this century. It appears that due to the rapid growth of English and Chinese Mandarin dominating the linguistics sphere, the world will lose the majority of its small, indigenous languages and we will be facing a future of fewer, more simplistic languages.

Until then, let’s immerse ourselves in the luxury of the outstanding linguistic opportunities we have access to at RHS, both through the wonderful diversity of our fantastically international student community and through the skills and commitment of our inspiring language department.

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.